The painting was in the collection of the Earls of Wemyss, Scotland, for over 250 years from around 1750.

Foreword by Rob Kattenburg

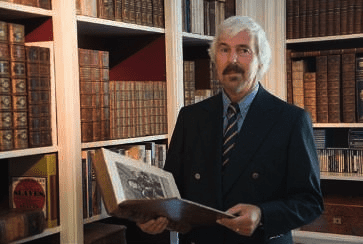

Introduction by Remmelt Daalder

Biography Willem van de Velde the Younger

The painting

The provenance of the painting

Material and technique by Martin Bijl

The Liefde and the Gouden Leeuwen

in a freshening wind

The evolution of the man-of-war in the third

quarter of the seventeenth century

The ships by Ab Hoving

The exploits of the Liefde

The life and career of Michiel de Ruyter

The life and career of Cornelis Tromp

The life and career of Pieter Salomonszoon

The Four Days’ Battle of 11-14 June 1666:

The Gouden Leeuwen and the loss of the Liefde.

The exploits of the Gouden Leeuwen

The life and career of Enno Doedens Star

The life and career of Frederik Willem,

Count van Bronckhorst Stirum

The galliot

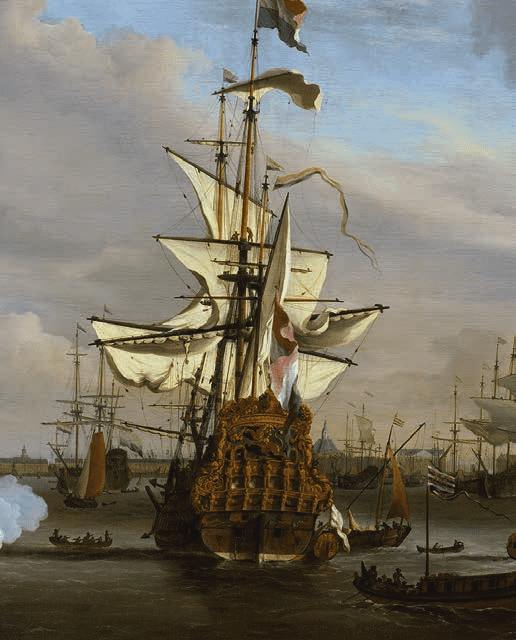

The relationship between the painting and Willem

van de Velde’s masterpiece, The ‘Gouden Leeuw’

on the IJ by Amsterdam in the Amsterdam Museum

Literature

Acknowledgements

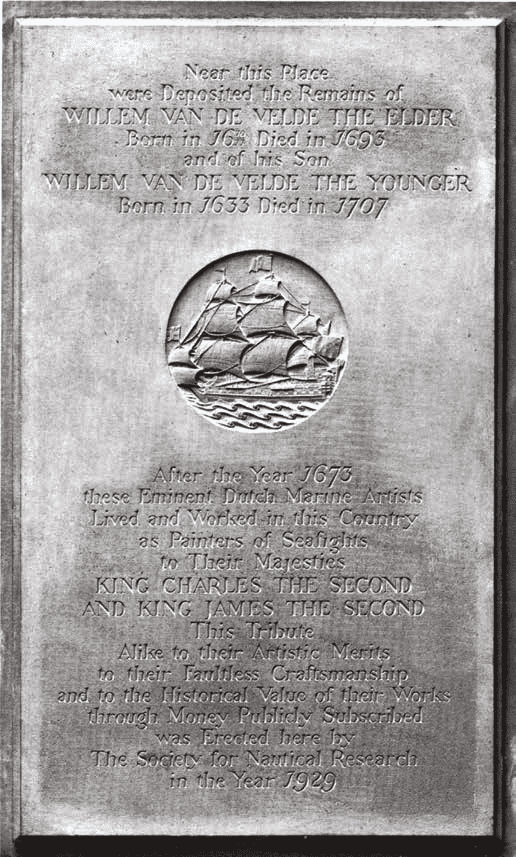

Rarely has an artistic family been as blessed with talent as the Van de Veldes. e father was a virtuoso ship draughtsman, and his two sons, his namesake Willem and Adriaen, were brilliant painters, each in his own genre: Willem as a marine artist and Adriaen as a master of bucolic landscapes.

Before the two Willems moved to England in 1672-1673 (Adriaen had died at the beginning of 1672) it was mainly the father who received one major commission after another. e younger Willem seems to have spent most of his time in the studio making small oil paintings, not for specific clients but for people who came in off the street in search of an attractive ‘sea piece’ to hang on the wall. at is the conclusion drawn from the small size of most of his pictures prior to 1672, rarely more than half a square metre. He only started making large paintings on a regular basis after going to live in England, and there he went to the other extreme with canvases up to 3 metres wide, such as his huge painting of the Gouden Leeuw at the Battle of the Texel in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, and the famous work in the Amsterdam Museum, e ‘Gouden Leeuw’ on the IJ by Amsterdam of 1686, which he painted while on a visit to the city.1

An artist would only make pictures that big if he was specifically asked to do so. Even the most successful painters would not have set up such a large canvas on their easels unless they knew beforehand that they had a customer for it. Van de Velde’s Dutch fleet assembling before the Four Days’ Battle of 11-14 June 1666, with the ‘Liefde’ and the ‘Gouden Leeuwen’ in the foreground, is 202.5 cm wide, making it one of his ten largest pictures, or at least of the ones that have survived. Only three of those ten date from his Dutch period,2 including the famous ship portrait in the Wallace Collection in London, which also features the Liefde. 3 Given its size, the Kattenburg painting must have been made on the express instructions of the patron, who was very probably Lieutenant-Admiral Cornelis Tromp, as explained by Rob Kattenburg elsewhere in this book.

at the patron chose to have the work painted by Willem van de Velde the Younger is perfectly understandable, but it is also odd. If it was indeed Tromp it could be explained by his good relationship with the artist’s father, who had already made several large pen paintings for him.4 But it was also daring of Tromp to award the commission to the son, who had so far painted little to order, to the best of our knowledge.

That was not his father’s fault, for he had already recommended his son in the early 1650s, when the Swedish admiral Carl Gustav Wrangel wanted someone to paint a battle between the Swedish and Danish fleets. As early as 1652 an intermediary was praising the young artist, just 18 at the time, as ‘Master Van de Velde’s son, a very good painter [...] in oils of sea pieces and battles’.5 Nothing came of that particular venture, but there is one other documented commission that certainly was executed. It was for two paintings of incidents in the Four Days’ Battle that Willem the Younger made for the Amsterdam Admiralty, as recorded in its resolutions for 30 September 1666: ‘to come to an agreement with Willem van de Velde to make two paintings of the two glorious battles against England’. Both of them are now in the Rijksmuseum and must have been completed at the end of the 1660s, in roughly the same period as the present picture. ere is one major difference from most later commissions though: they are only 81 cm wide.6

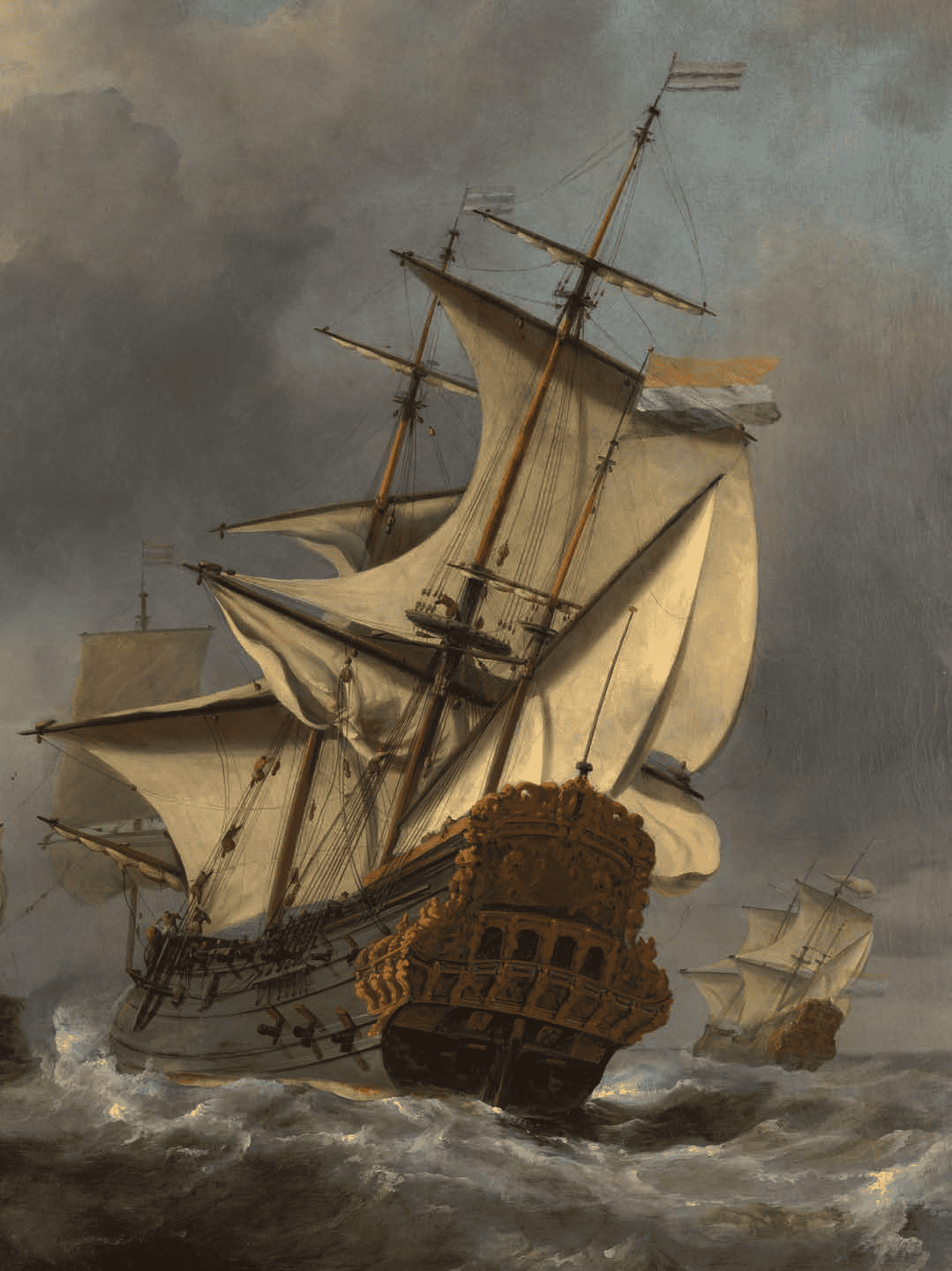

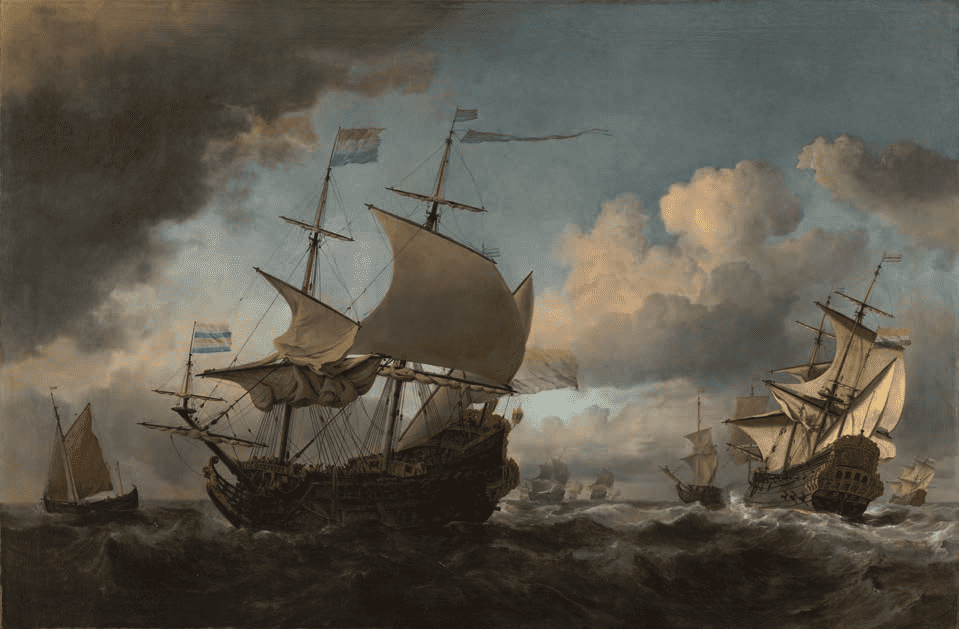

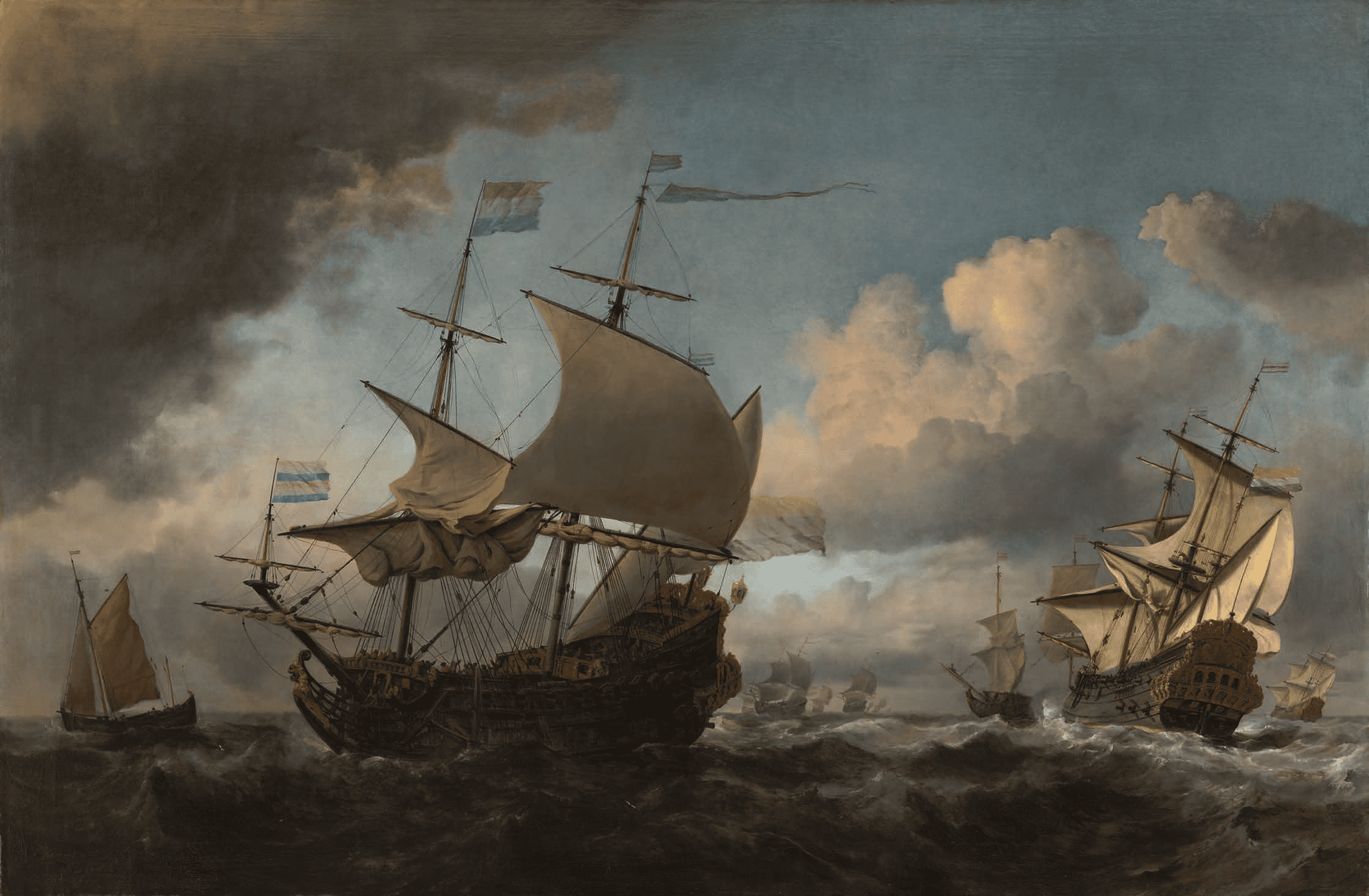

The painting of the Liefde and the Gouden Leeuwen marks a new stage in Van de Velde’s development. Not only did he start working on a larger scale around 1670, but his style was also evolving. He had previously excelled in sublime, calm seas and coastal waters, but now the elements are playing a far more tempestuous role. We are witnessing a moment just before a storm breaks. e wind is gathering strength, foam is being blown off the crests of the waves, and the last rays of sunshine are casting an ominous light on the sails. Bearing down from the left is the heavy squall that will be battering the ships in a moment or two. is is an unusual kind of scene for Van de Velde’s Dutch period. In England he quite often depicted ships battling the elements like this.

His introduction of turbulent seas has long been a reason for assuming that there was a close relationship between the Van de Veldes’ studio and their fellow townsman Ludolf Bakhuizen, who indeed produced many stormy seascapes around the time of this painting.

Michael S. Robinson, the compiler of the monumental catalogue of the paintings of the Van de Veldes, believed that Bakhuizen and Van de Velde collaborated on this and similar pictures, with Bakhuizen contributing the rough sea and thundery skies and Van de Velde the ships.7 Although understandable, that is an incorrect assumption.

It is more likely that there was a change in the taste and preferences of the customers, with the result that Van de Velde adopted Bakhuizen’s dramatic style but applied it with his own looser manner. Nothing is known for certain about any collaboration with other artists in this period, either as assistants or pupils.8

This painting is actually a ship portrait (or rather double portrait), but it is a very lively variant, with all the details of an approaching storm and the secondary elements of the other vessels. And it is also innovative as a ship’s portrait. Compared to the stately double portraits of almost motionless ships that the studio had previously been selling, these are ships and crews in action. An experienced old sea dog like Cornelis Tromp would have felt very much at home with this painting.

Dr Remmelt Daalder

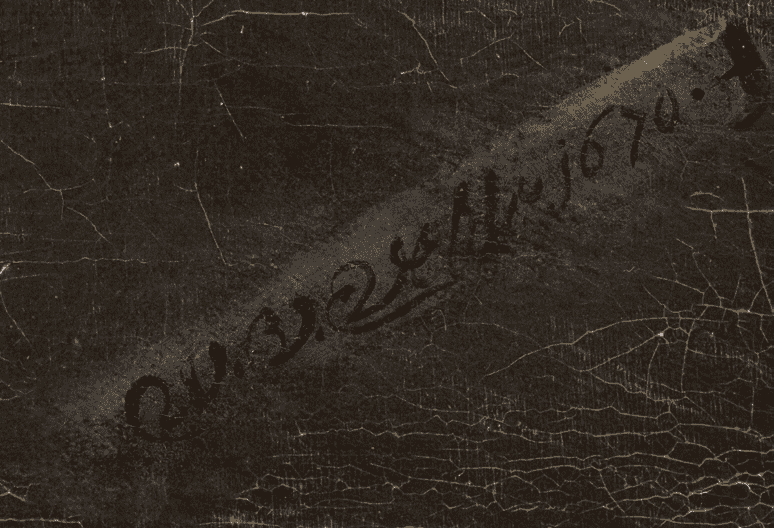

Fig. 2

‘I. Smith fec. 1707’, after a painting by Sir Godfrey Kneller Portrait of Willem van de Velde the Younger

Mezzotint, 34.9 x 25 cm

Amsterdam, Scheepvaartmuseum inv. no. A.0484(01)

1. Greenwich, National Maritime Museum, inv. no. BHC0315, and Amsterdam Museum, inv. no. SA7421, 300 and 316 cm wide respectively.

2. Paintings that are not quite as wide, between 150 and 200 cm, also date almost exclusively from after 1672. With thanks to Sander Bijl for documenting the sizes of the Van de Veldes’ paintings.

3. London, Wallace Collection inv. no. P137.

4. Remmelt Daalder, Van de Velde & Son, marine painters. e firm of Willem van de Velde the Elder and Willem van de Velde the Younger, 1640-1707, Leiden 2016, p. 87ff.

5. Ibidem, p. 110.

6. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. nos. SK-A-438 and SK-A-439; Michael S. Robinson, Van de Velde. A catalogue of the paintings of the Elder and the Younger Willem van de Velde, 2 vols., London 1990, pp. 148 and 153 (nos. 109 and 110). Daalder 2015, pp. 96-97.

7. Another example is a picture in the National Gallery of South Africa; Robinson 1990, p. 832.

8. With the possible exception of Hendrick Dubbels, who may have had a hand in the production of pen paintings and works in oils. However, in this particular case there is no reason to suspect his involvement. See Daalder 2015, p. 50.

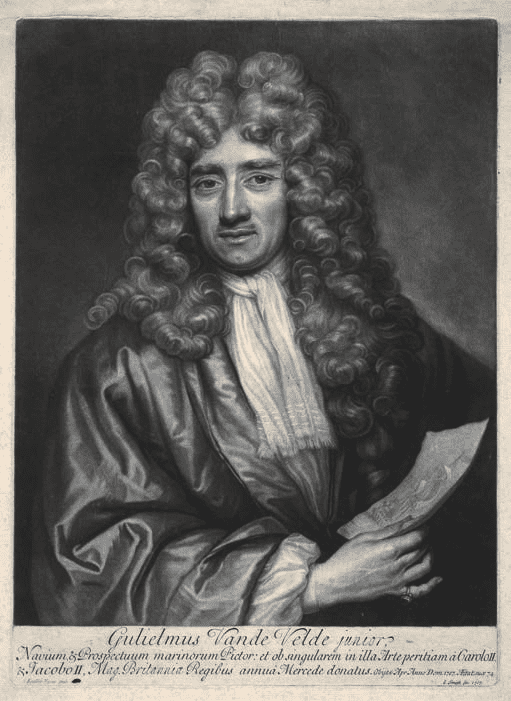

Fig. 3

Lodewijk van der Helst (Amsterdam 1642-1684) Portrait of Willem van de Velde the Younger (1633-1707), painter

Oil on canvas, 103 x 91 cm

Unsigned, c. 1670

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. SK-A-2236

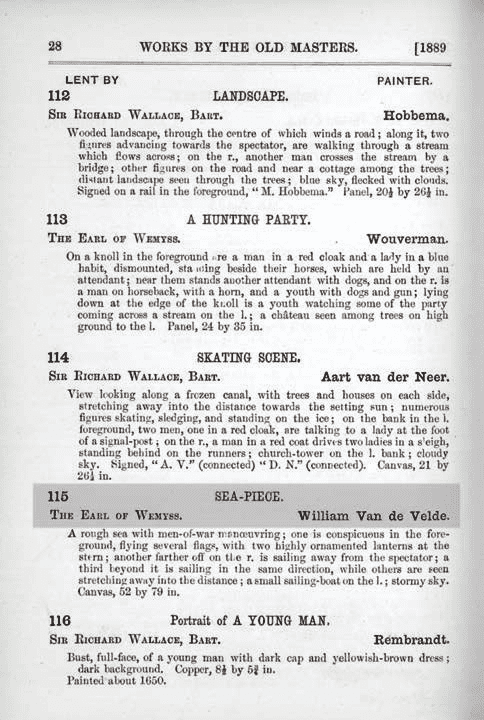

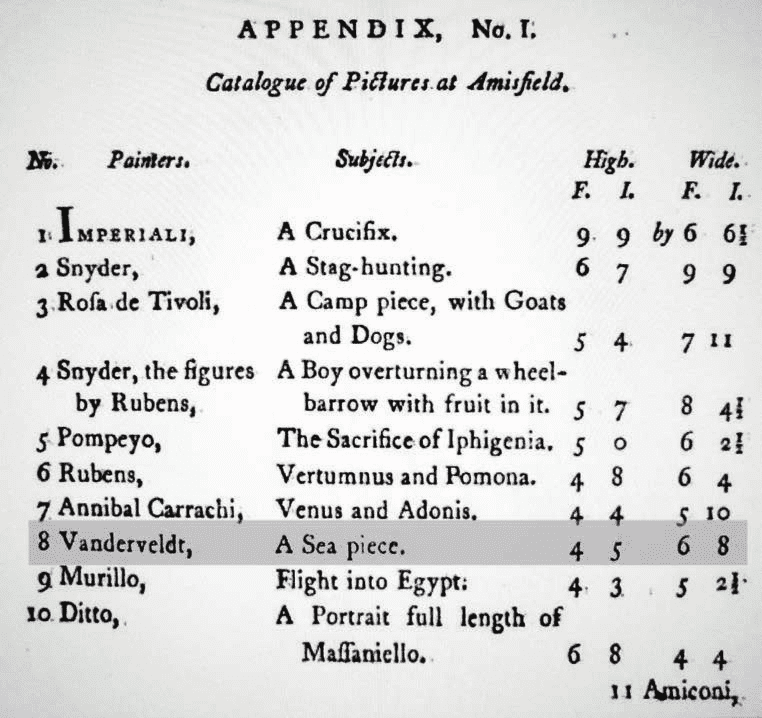

The earliest known source to mention Van de Velde’s seascape is a handwritten catalogue of 1771 of the picture collection of the Earl of Wemyss in Amisfield House.The original manuscript is probably lost, because only a printed version survives. It was included by the Reverend Dr George Barclay in 1792 as an appendix to his article

on the places of interest in the parish of Haddington. He relates how his parish, 17 miles east of Edinburgh, bordered Monkrigg. To the east was the Amisfield estate of Francis Wemyss Charteris, 7th Earl of Wemyss. Amisfield was a majestic, modern house that thee earl had built 25 years before. The main building was 109 feet long and 77 wide.There were many large rooms, and ‘Yhe gallery contains many capital paintings, some of them by the First masters; particularly a crucifixion by Imperiali, Venus and Adonis by Anibali Carraci, the sacrifice of Iphigenia by Pompeio, a sea piece by Vandervelt. … He [the earl] was so obliging as to favour me with a catalogue of all his paintings and portraits, and it is annexed in the appendix No. 1.’

The earl’s collection of paintings consisted of 133 works, most of them by old Italian and Dutch masters.There were also 15 contemporary family portraits, including one of the earl by the famous Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792), and another of the earl and his wife, Lady Catharine Gordon (fig. 8), by the Scottish portraitist Allen Ramsay (1713-84).

Fig. 8

Allen Ramsay, Double portrait of Francis Charteris, né Wemyss, and his wife Catharine Gordon, c. 1745. Gosford House Collection

Van de Velde’s scene of ships in a stiff breeze on a choppy sea is catalogued under number 8 as measuring 4 feet 5 inches high and 6 feet 8 inches wide, approximately

134.6 x 203.2 cm, which are almost exactly the present dimensions of the picture. In the printed version of the catalogue it is listed among the first and undoubtedly most expensive works in the collection: large figure pieces by Italian Renaissance masters like Veronese and Carraci, two works by the seventeenth-century Spanish painter Murillo, and others by the Flemings Rubens, Jordaens and Snijders (fig. 7).

Much of the collection at Amisfield must have been put together by Francis Charteris (1723-1808), the 7th Earl. The social elite in the eighteenth century took a great

interest in the art of the Renaissance, and after completing his education Wemyss went on the Grand Tour and visited Rome and Florence. One also gets the impression that he became acquainted with the Dutch Old Masters during his travels, for in 1771 he had more than 40 paintings by Dutch artists such as Rembrandt and recognised landscapists like Jacob van Ruisdael, Salomon van Ruysdael, Van der Neer, Hobbema and Van Goyen.1 The View in Holland by the relatively unknown Jan ten Compe (1713-1761), an Amsterdam art dealer and painter of city views, which is listed under no. 44, was almost a contemporary work in 1771, so there can be no doubt that the earl was very fond of Dutch landscape painting. Apart from the large Van de Velde, it seems from the catalogue that he only had two other seascapes, both small, by Ludolf Bakhuizen.

The Wemyss Collection was greatly enlarged in the nineteenth century by Francis Richard Charteris (1818- 1914), the 10th Earl. In addition to being a passionate collector of old Italian art, he acquired a harbour scene by Willem van de Velde the Younger, which has been at Amisfield since 1835.2

THE EARLS OF WEMYSS

In 1511 Sir David Wemyss received a charter from the Scottish King James IV converting all his lands into the Barony of Wemyss. He lived in the fifteenth-century Wemyss Castle in Fife, which is still the seat of the Wemyss clan. His grandson, Sir John Wemyss, was a confidant of Charles I of England. He was raised to the Scottish peerage in 1628 with the honorary title of Lord Wemyss of Elcho, and in 1633 was made Earl of Wemyss. He was succeeded by his son, the 2nd Earl, who had no male heirs but was allowed to pass the title on to his daughter Margaret. She married her third cousin James Wemyss, Lord Burntisland, to whom she bore a son and two daughters. The son, David Wemyss (1678-1720), became the 4th Earl. He took his seat in the House of Lords in London in 1705 and was an

adviser to Queen Anne. In 1706, some two years before the union of Scotland and England, he was appointed Lord High Admiral of Scotland. It was a very honourable post, but there was hardly a professional Scottish navy to speak of. In times of need it was cobbled together out of armed merchantmen, mercenary vessels and freebooters.

It was only at the end of the Nine Years’ War (1688-97) that the Scottish admiralty built three small men-of-war to protect the merchant fleet from the French: the 32-gun Royal William and two 24-gun frigates, which were absorbed into the Royal Navy with the Act of Union of 1707. After the merger of the two admiralties Wemyss was appointed Vice-Admiral of Scotland. He married three times, and had two sons by his first wife, Lady Anne Douglas, daughter of William, Duke of Queensberry. The eldest one, also called David, died unmarried at the age of 17, so it was the second son, James, who succeeded him in 1717 to become the 5th Earl. In 1720 James married Janet Charteris, daughter of the immensely rich Francis Charteris of Amisfield, a colonel in the foot guards, an infamous drunkard and gambler who only escaped execution for rape thanks to the intervention of some influential friends. The marriage, though, was not unwelcome, for the Wemyss clan was on the brink of bankruptcy.

James and his wife had three sons and four daughters. The eldest son, James, called Lord Elcho in the records, who also bore the title of the 6th Earl, was involved in the Jacobite uprising of 1745 against the British crown and was forced to flee to France, where he died childless in 1787. The couple’s third son, another James, was a naval lieutenant in his youth. He became the owner of Wemyss Castle on the reversal of the confiscation of the possessions of his older brother David. at made him the ancestor and chief of Clan Wemyss of Wemyss, which survives to this day.

The couple’s second son, Francis, became the ancestor of the later Earls of Wemyss. He succeeded David to become the 7th Earl in 1771. His future was assured at an early age when he took the name Charteris from his mother in February 1732, which made him the heir of his grandfather, Colonel Francis Charteris, whose estate was

said to be worth 300,000 pounds. After Francis completed his education at Eton College he went on the Grand Tour through Europe before returning to Scotland in 1744. A

year later he married Catherine Gordon, who bore him five children.

Francis Charteris died at Gosford House in 1808 at the age of 85, outliving his only son by a few months. In 1826 parliament gave its approval for the vacant earldom to pass to his grandson, Francis Wemyss Douglas (1772-1853), who became the 8th Earl of Wemyss. He had already inherited the title of 4th Earl of March from his mother in 1810, so he was now officially Francis Wemyss Douglas, Earl of Wemyss and March.

Both titles passed to his son Francis WemyssCharteris (1796-1883) in 1853, the 9th Earl of Wemyss and March, to the 10th Earl in 1833, Francis Richard Charteris, also known as Lord Elcho (1818-1914), to the 11th Earl, Hugo Richard Charteris (1857-1937) in 1914, to the 12th Earl, Davis Charteris (1912-2008) in 1937,

and finally to James Donald Charteris, the present 13th Earl of Wemyss and 9th Earl of March (b. 1948), who is better known as Lord Neidpath.

AMISFIELD HOUSE AND GOSFORD HOUSE

By taking the name Charteris in 1732, Francis inherited his grandfather’s fortune, which enabled him to buy the Amisfield estate in Haddingtonshire. In 1755-1760 he

had a house built there by Isaac Ware in a classic Palladian style. It was a massive symmetrical building in red sandstone measuring 109 feet long and 77 wide, with four floors and a classical temple pediment supported by four columns. e house, which was the purest imitation of the style of the Italian architect Andrea Palladio (1508-1580) in Scotland, fell into disrepair in the nineteenth century and was demolished in 1928. All that remains on the estate, which is now a golf course, are the stables, a few outbuildings and a walled garden (fig. 9).

It appears from the 1792 article by the Reverend Barclay that Francis Charteris’s collection of paintings was then in Amisfield House, but at the time when the article was published the earl had commissioned the famous Scottish architect Robert Adam to build him a new country house in Gosford, near the village of Longniddry in East Lothian, on an estate he had bought in 1784 on the River Forth some 6 miles north-west of Amisfield House and 13 miles west of Edinburgh (fig. 10).

Building work on Gosford House started in 1790, but as a result of numerous setbacks it was never completed. Adam died in 1792, and it soon became apparent that there were problems with the materials being used and that the house was very damp. As a result Charteris, and later his grandson and successor, the 8th Earl, lived in Amisfield House and Old Gosford House, a smaller

Fig. 9

Amisfield House c. 1880. It was built around 1755 by Isaac Ware in a Palladian style and was commissioned by Francis Charteris, the 7th Earl of Wemyss. It was the family home for almost the whole of the nineteenth century, and was demolished in 1928.

seventeenth-century building on the same estate. According to a travel guide to Scotland, the most important paintings in the Wemyss Collection were still in Amisfield House in 1818. ‘The gallery contains many capital paintings, by the first masters’, such as a Vertumnus and Pomona by Rubens that was valued at 800 guineas, a Crucifixion by Imperiali, a Sacrifice of Iphigenia by Pompeio, a Barocci Venus and Adonis, a Flight into Egypt by Murillo, Poussin’s Baptism, ‘a fine Sea-piece by Vanderveld … and many others’.3 It is not known precisely when, but the Van de Velde must have been installed in Gosford House before 1830, for in that year a guest of the earl’s describes seeing the picture collection. Gosford House, he writes, was a stately country house in the Greek style with several connecting rooms that were specially designed for ‘the exhibition of his pictures to the best advantage’.4 The artists whose works he saw there included Claude Lorraine, Salvator Rosa, Leonardo da Vinci, Murillo, Rembrandt, Snijders, Cuyp, ‘and Vanderveld’. He also relates that the earl was not living in the house, which was in such poor condition that ‘It is now left standing only for the accommodation of a part of the paintings’. An art critic also wrote in 1830 that Gosford House served solely as an exhibition venue: ‘the three large public rooms, which constitute almost the whole body of the house, are occupied by the late Earl’s large collection of paintings. These rooms - three in

Fig. 10

Gosford House, c. 2013. The house was built for Francis Wemyss in 1790 after a design by the famous Scottish architect Robert Adam. It was ideally suited for displaying the paintings, but was only lived in for a few decades. Its original wings had become so dilapidated by 1830 that they had to be demolished. Photo Stephen Lee.

number - are very large and beautifully proportioned’. The three galleries were lit on one side by large windows, and had been designed to show off the paintings to the best effect. It is for that reason that Gosford House is occasionally referred to as the first building with a museum function to be built in Great Britain.5 Visitors could view the collection by appointment, and the earl also invited artists from Edinburgh to come and ‘take copies from his pictures’, although he was rarely taken up on his offer.6 In 1834 the Van de Velde ‘in the collection of Lord Wemyss near Edinburgh’ was first described in detail by the art dealer John Smith, who had catalogued some 250 works by Willem van de Velde the Younger at home and abroad. He did not see the marine in Gosford House with his own eyes, and had to admit that his description was based on ‘a sketch in pencil’, and it seems to have been one that was not all that accurate. For instance, Smith stated that ‘the sailors are firing a salute’ on the ship sailing away from the viewer, although it is clear from the painting itself that this was nothing more than water splashing up from the bow.7

The painting was still hanging in Gosford House in 1854, when the German art historian Gustav Waagen was given a short tour of the house and saw Van de Velde’s seascape in the drawing room. It hung among 20 other works of every kind, such as a Baptism of Christ by Poussin, a biblical scene by Murillo, a portrait by Velázquez, and pictures by several Dutch artists, Van Goyen and Jacob van Ruisdael among them. Waagen described some 40 paintings in the Wemyss Collection. ere were more hanging elsewhere in the house, but he could not see or judge them properly in the poor lighting. He described the Van de Velde as ‘A slightly agitated sea. On the right, in the shadow of a cloud, is a two-masted vessel; on the left, in the middle distance, a three-masted vessel in sail. Quite on the right are more vessels and dark clouds. A large picture of peaceful effect and very careful execution’.8 Although the description is not very accurate as regards the number of masts and the positions of the dark clouds, there can be no doubt that the picture that Waagen saw was this one with the Liefde and the Gouden Leeuwen.

Waagen inspected the collection of paintings in a few rooms of the main building, because the original wings that Adam had built on either side had probably already been demolished around 1830. After 1890 the architect William Young was commissioned to rebuild them in a playful Renaissance/Baroque style that can still be seen today. It was during this rebuilding work that the imposing marble hall with staircase was built in the south wing, leading to a surrounding picture gallery (fig. 11).

The Dutch art historian Hofstede de Groot visited the renovated Gosford House and wrote that Waagen had seen the picture collection while it was ‘still in an old and poorly lit house. It is now housed in a new, spacious and brightly lit palace in Italian Renaissance style, and most of the pieces are in good view’.9 Hofstede de Groot did not pay any special attention to the Van de Velde, merely referring to it as ‘ships in a storm’.10

Fig. 11

Gosford’s famous marble hall was created around 1890, when the two wings of the house were rebuilt.

ACQUISITION

It seems almost certain that Van de Velde’s marine was acquired by Francis Charteris, the 7th Earl. Although his grandfather, Vice-Admiral David Wemyss, clearly had some affinity with the sea, the family’s financial circumstances at that time make it unlikely that he bought the expensive painting and passed it down to Francis Charteris by descent. Francis’s father’s marriage to Janet Charteris was also undoubtedly one of convenience, with a member of the impoverished aristocracy marrying a rich, upperclass heiress. It very much looks as though the immensely rich Colonel Charteris arranged matters so that his daughter would ensure that his family name survived in the aristocratic Wemyss family, and that at the same time the latter was spared the scandal of a bankruptcy. There is not the slightest evidence that the colonel, whose rakish life was the subject of a contemporary biography, had an important collection of paintings, or even took the slightest interest in the arts, which makes it improbable that he ever bought the Van de Velde and that his grandson inherited it. The likeliest scenario for the acquisition is that Francis Charteris started spending the money he had inherited from his grandfather in order to live as befitted an earl. That is apparent not only from the building of Amisfield House around 1755 and of Gosford House in 1790, but also from the fact that he had already built up a sizable collection of more than 100 pictures by 1771. It was not unusual for young aristocrats to buy art on the Grand Tour and send it home, but it is not known whether Charteris did so as well. So far not a single painting from the 1771 catalogue can be traced back with any certainty to an earlier European collection or to a description in an auction catalogue. However, there can be no doubt that Francis Charteris, like most aristocratic collectors, was offered pictures by professional art dealers, who bought work in London at Sotheby’s (1744) and Christie’s (1766), or on the continent. e Earl of Wemyss continued improving and enlarging his collection till the end of his life. For instance, a visitor to Amisfield House in 1795 reported that ‘Lord Wemyss is 73 years old, and has lately experienced a considerable loss in pictures and wine, which formed part of the cargo of a ship, captured by the French on its passage from London to Edinburgh’.11 It is known from the correspondence of the Scottish art dealer William Buchanan (1777-1884) that he was in close touch with the earl, and that he had offered him work by a French artist called Claude (Lorrain, perhaps?), which, he said, the earl had been after for years. It is worth noting in this connection that the Dutch artists’ biograph Arnold Houbraken

noted around 1718 that English art dealers had descended on the Netherlands en masse in order to buy up the work of Willem van de Velde the Younger and carry it off toEngland. However, it had become so scarce in his native country ‘that one does not see much of the same’.12 In other words, it is very possible that Van de Velde’s majestic seascape had already ben taken to England by the art trade in the early eighteenth century, and was later bought by Wemyss for the decoration of Amisfield House.

It was not until the 1950s that Gosford House, which served as a sort of exhibition hall for several decades after it was built, was permanently inhabited by the 12th Earl. He died in 2008, and Lord Neidpath, his son and successor, has shown no interest in moving there, living instead with his family in Stanway House in Gloucestershire in England. So Gosford House is no longer a home, but to compensate it has regained a public function. Since May 2010 the country house can be hired for galas, weddings and other hospitality events, and in the summer its collec-tion of paintings is open to the public, free of charge.

1. Archaeologia Scotica: or Transactions of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, vol. 1, Edinburgh 1792: ‘Account of the Parish of Haddington, by the Rev. George Barclay’, Section I, pp. 40-49, esp. p. 46. See pp. 77-84 for the appendix with the picture catalogue.

2. J. Smith, A catalogue raisonné of the works of the most eminent Dutch, Flemish, and French painters, vol. 6 (1835), p. 394, no. 259. It was bought in 1835 from the collection of W. Moorland Esq., Edinburgh.

3. The traveller’s guide through Scotland, vol. 1, (1818), p. 116.

4. C.S. Stewart, Sketches of society in Great Britain and Ireland, vol. 2 (1834), pp. 108-109. e passage is from a letter that Stewart wrote in 1832.

5. G. Waterfield, Palaces of art: art galleries in Britain 1790-1990, p. 30.

6. ‘Gosford House and its paintings’, The Edinburgh Literary Journal; or, Weekly Register of Criticism and Belles Lettres (1830), p. 218.

7. Smith, op. cit. (note 2), vol. 6, p. 338, no. 63: ‘Frigates and other Vessels in a Breeze, e principal object is a large ship of war, with her broadside to the spectator, sailing along the front: beyond her, and on the opposite side, is a second vessel, of a similar description, from which the sailors are firing a salute. Other frigates are seen at more remote distances. 4 ft. 6 in. by 6 ft. C[anvas]. Described from a sketch in pencil. Now in the collection of Lord Wemyss, near Edinburgh’.

8. G.F. Waagen, Galleries and cabinets of art in Great Britain, vol. 4, London 1857, p. 438.

9. C. Hofstede de Groot, ‘Hollandsche kunst in Schotland’, Oud Holland 11 (1893), pp. 211-228, esp. p. 218.

10. Ibidem, p. 220.

11. J.H. Manners, Journal of a tour to the northern parts of Great Britain, London 1813, p. 162. Entry for 24 August 1796.

12. A. Houbraken, De groote schouburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen, vol. 2, (1719), p. 324.

‘To make the painting very durable apply the following mixture to the glued reverse. Grind umber with linseed oil, almost as liquified as the oil, then heat this mixture gently over a low flame until it has achieved the consistency of syrup, then apply with a brush. It dries quickly and will prevent damage to the canvas, even when up against a damp wall.’1

The thin, umber-coloured layer on the back of Van de Velde’s Dutch fleet assembling before the Four Days’ Battle of 11-14 June 1666, with the ‘Liefde’ and the ‘Gouden Leeuwen’ in the foreground, seems to have lived up to De Mayerne’s promise of durability, for despite its dimensions of 133.5 x 202.5 cm the canvas has never been relined. at is not only highly unusual but also perfectly justified. The quality of the 345-year-old canvas suggests that it could survive for twice that period without a backing canvas. By comparison, the reverse of a slightly smaller Dutch painting 27 years older that was conserved at the same time was never treated in any way, and that canvas is now very brittle and fragile.

THE GROUND

Amsterdam primers supplied standard grounds with a grey mid-tone over a reddish brown base layer, unless there were special wishes, such as the quartz grounds that Rembrandt used from The night watch onwards, or the ‘whitened’ canvases and panels for the pen paintings of Willem van de Velde the Elder. That is also the case with this canvas.

Amsterdam primers supplied standard grounds with a grey mid-tone over a reddish brown base layer, unless there were special wishes, such as the quartz grounds that Rembrandt used from the night watch onwards, or the ‘whitened’ canvases and panels for the pen paintings of Willem van de Velde the Elder. That is also the case with this canvas.

UNITS OF MEASURE

In 1652 Willem van de Velde the Elder wrote to tell the Swedish Count Carl Gustav Wrangel that he could make pen paintings up to 25 feet (more than 7 metres) long.In his covering letter Michel Le Blon went even further by saying that 30 feet was also possible, which is more than 8½ metres. The sizes of large canvases were evidently given in feet, unlike the mass-produced commercially available, primed canvases and panels up to approximately 1.5 metres, which had fixed height to width ratios and were sold under names like Salvator, Grote Stooter and Daeldersmaet. Nor were large canvases stocked readymade by artists’ suppliers; they were ordered individually.The unpainted tacking edges of the Dutch fleet are still present, so the dimensions are known fairly precisely. With a painted width of 204 cm it seems that the canvas was not ordered by someone in Amsterdam but in the present-day province of South Holland, for that is an exactmultiple of 78 Rhineland feet. In contrast to small sizes, the height to width ratios of large canvases would certainly not have been fixed. They would have been determined by the size of the wainscoting or the available wall space. Or, as here, by the standard width of a roll of canvas, which in this case would have been 2 ells, for the selvedges at top and bottom are still present, giving a total width of the roll (that is to say the height of the painting plus the tacking edges) of approximately 140 cm. That would have determined the painted height. The tacking edges would have left a maximum of 52 Rhineland inches over, which precisely matches the painted height of a little more than 136 cm.

THE PAINTING

Towards the end of his life Van de Velde mused that ‘there are many important points to be considered when embarking on a painting, whether one wishes to make it mainly dark or mainly light. The first point to be considered is the direction of sun and wind, as well as their strength or moderation, in order to make the right choice. Further the sketches of dispositions or ships under sail, as in this case, or many other matters from which I have to choose at the start.’2

Since the Dutch fleet was almost certainly commissioned by a client there were several things that Van de Velde did not have to think about. The size of the canvas was one; it was decided for him. And the choice of subject would also have been made by the client. In a force 5 freshening wind the crews are making haste to raise the anchor and trim the sails. The kind of waves in the foreground of the picture confirm that the location is not far from the coast. If there was anyone able to depict the right kind of waves it was Van de Velde. He studied the behaviour of water in motion and the fall of light in all kinds of weather right up until the end of his 74-year life. Quite apart from the fact that he could use that knowledge to define a location, the size of this canvas allowed him to combine it with another device. Viewing water against the light makes it opaque, and conversely looking into it with the light makes it easier to see beneath its surface.

Van de Velde captured that effect by using a lot of opaque paint on the left and an interplay of transparent, semitransparent and opaque paint on the right, emphasising the vast sweep of the spectacle. He also made the water in the middle ground look more lively by adding patterned reflections. It would have been more difficult, if not impossible, to achieve such a stirring image in a smaller painting. This was Van de Velde’s first large commission, so it was his first opportunity to explore such theatrical effects, and he seized it with both hands.

Before actually putting brush to canvas he would have made a composition sketch. Since the central perspective system was unsuitable for scenes of this kind, Simon de Vlieger and Willem van de Velde the Elder had developed a completely new perspective method for seascapes that was perfected by Willem van de Velde the Younger.3 It would be going too far to explain it in detail here, but the following are the main characteristics.

1. The horizon is drawn at the draughtsman’s eye level.

2. All the objects in the scene are crossed by the horizon at the same height from the ground plane.4

Although there is no hard evidence that Van de Velde really did use his own system in this picture, there are strong indications that he did. Four of the ships were underdrawn: the galliot on the left, the Liefde beside it, the Gouden Leeuwen on the right, and the ship in front that is largely masked by the Gouden Leeuwen and the water splashing up from its bows. Van de Velde explained in one of his instruction drawings that he based the construction on a vertical line drawn upwards from the centre of the bottom of his objects, in this picture from the waterlines of the ships.5 In the case of the galliot and the Liefde a black indicator line running precisely along the imaginary waterline can be seen through the thin paint. is is the most important starting point for the perspective construction. Plus, of course, a thorough knowledge of the sizes and proportions of each individual ship. It is well known that the Van de Veldes had a vast stock of drawn ship portraits. In all probability a portrait of Van de Velde in his studio by Michiel van Musscher (fig. 12) shows some of those drawings being put to practical use for a painting. It would have been on the basis of that initial indication that a loose sketch, in white chalk for instance, could have served as the basis for a precise underdrawing with the brush. Such an underdrawing can be seen through the paint film at various points where Van de Velde deviated from it during the painting stage, one of which is by the mainmast of the Liefde.

The underdrawn version was a little too long, as can be seen through the sail, and the original position of the lowest yard is still visible through the mizzen (the large slanted sail on the rearmost mast). It was only then that Van de Velde could begin painting, and he did so in the same way that all his seventeenth-century colleagues did: working from back to front. So the sky was painted

Fig. 12

Michiel van Musscher

Portrait of a painter in his studio

Signed ‘Musscher/ Pinxit 16...’ca. 1665-1667

Oil on panel, 47.6 x 36.8 cm

Liechtenstein, The Princely Collections, Vaduz–Vienna

first, with reserves left for the ships and their sails. The haze that veils the drawn elements that are visible but do not match the painted versions shows that the masts were simply overpainted, preserving the rapidity of the brushstrokes around the ship as well. The fact that they showed through the paint layer was utilised to work on them further. This was followed by the first design of the waves, after which the ships were painted in their base colours. After that layer had dried the ships and waves could be worked up in detail. The rigging was then added, not with mechanical aids, as is sometimes thought, but freehand. It was in this stage that all the other ships were added on top of the paint surface. Finally, the painting was ‘retouched’, as it was called, that is to say with a few depths but above all highlights and improvements. One good example of an improvement is the nonchalant addition of a dab of light paint between the hull of the galliot and its mainsail. During the painting of the sky based on the drawing, too much of a reserve was left at this point, and even despite the correction there is still grey ground visible around it. The sky on the far right painted loosely over the horizon line was never corrected by overpainting it with the colour used for the sea.

Martin Bijl

Fig. 13

Detail of the Liefde (fig. 5)

Before cleaning

1. Ernst Berger (ed.) De Mayerne Manuskript, Munich 1901, p. 326. Ms. P. 147 verso: ‘Pour rendre le tableau tres durable, sur les revers bien collé [...] mettés la mixtion suyvante: Broyés de la terre d’ombre avec de l’huile, puis faites bouillir cette mixtion a lent feu remuant tousjours jusques á consistence de syrop, & vous and servés avec la boisse. Cela se seche incontinent, & empesche que la toile mise mesment contre une muraille humide ne se pourrisse.’

2. Margarita Russell, Willem van de Velde de Jonge, Bloemendaal 1992, pp. 87-88.

3. For a detailed explanation of their system see R. Ruurs, ‘Even if it is not architecture,’ Simiolus 13 (1983), pp. 189-200.

4. Ibidem, p. 196.

5. Ibidem, p. 196.

Fig. 14

Detail of the Liefde (fig. 5)

After cleaning

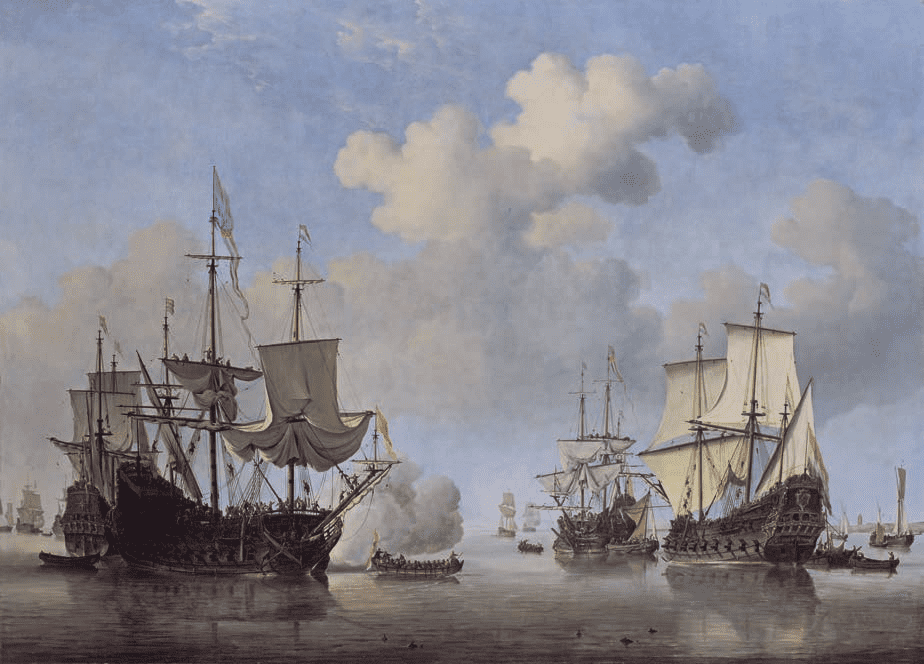

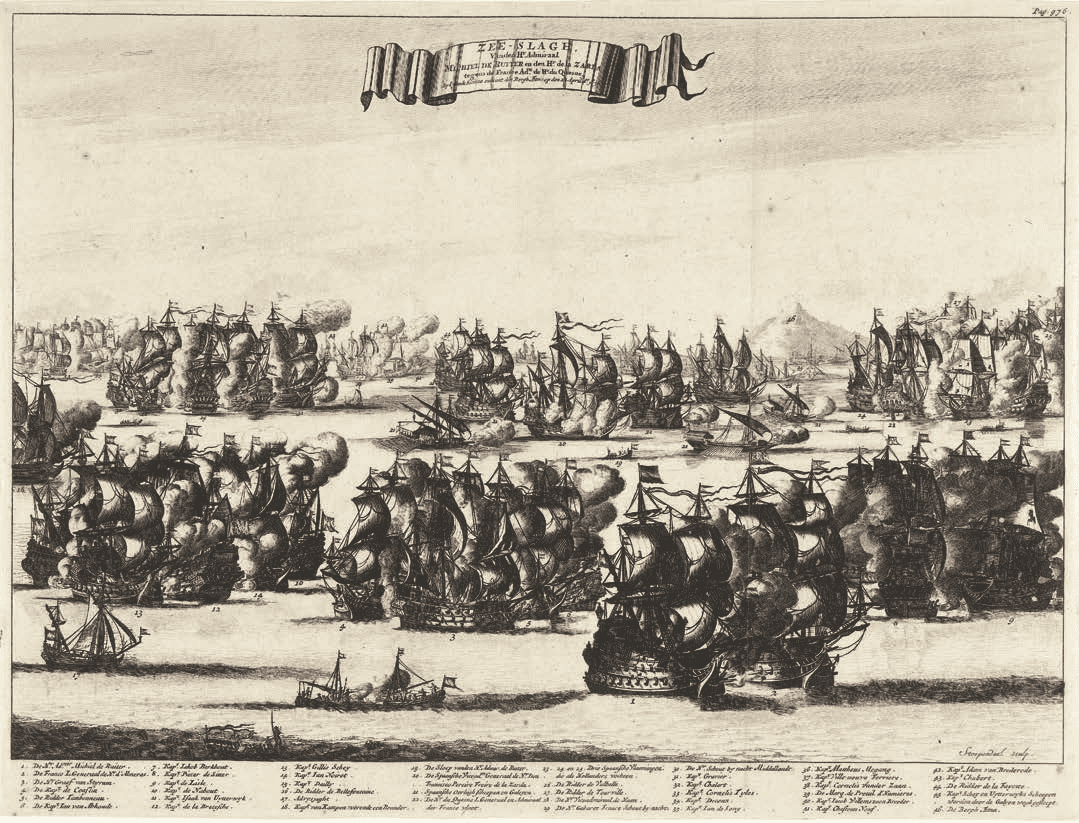

INTRODUCTION

Ships in a freshening wind is what we see in this large painting of 1670 by Willem van de Velde the Younger. But what are we really looking at? What has Van de Velde

actually depicted? Knowing him and his work, this is no arbitrary moment in the history of the two prominent ships. What are their names, anyway? And what are the other ships in the picture? And above all, what is this particular event? ese are the questions that arise at the first sight of this impressive masterpiece. So let’s try and analyse what is going on.

THE WEATHER

The detached observer gets the idea that the canvas depicts stormy weather. That is only partly true. All the ships still have their topsails set. they are the large stretches of canvas above the lower ones, but the topgallants above them have already been reefed. In seaman’s terminology this was done when the wind had reached the strength of a ‘reefed topgallant breeze’, in other words a strong breeze that is the equivalent of the modern wind force 5. That is not quite a storm, but it seems that there will soon be a dramatic change in the weather. A squall is approaching from the left and the wind is freshening, as can be seen from the ship in the distance on the far right, which is hastily letting fly the sheets of its main topgallant. The large ship on the right with its stern to the viewer is already lowering its fore topsail. A reefed topsail breeze is the equivalent of wind force 5-6.

In other words, the artist has depicted his ships in weather that is rapidly deteriorating and is about to get much worse when the squall hits. This gives the picture the dynamic nature of a disaster about to happen. A disaster, as we shall see, that was soon to overwhelm the central ship in real life.

THE SAILS

Crowds of people are milling about on the deck of the large ship in the foreground. Men are running back of forth, and some are in such a hurry that they don’t even take the time to use the steps and ladders to get from one deck to the next but are clambering over railings. Many of the figures are gesticulating wildly. What’s going on? Several of the ship‘s sails are filled, and the main topsail is stretched taut in the gathering wind, as is the triangular sail on the mizzenmast. The ship is close hauled, with its yards braced hard to the port side. Sails set like that will turn the bow even further into the wind, but that is being prevented for the moment by what is going on with the foremast. The wind has caught the front of the fore topsail and has slammed it back against the mast top, the concealed outline of which has been captured beautifully. The foresail below it is still unfurling. It can be seen that the sails are being set, not taken in, from the fact that no one has been sent up to the yards, which would otherwise have been full of men sitting astride them doing the dangerous work of furling the sail, with one hand for themselves and the other for the ship. It seems, then, that this is a moment of departure.

THE ANCHOR

That is borne out by what is going on in the bow. Crewmen are busily stowing a half-raised anchor against the side of the hull in an operation known as catting the anchor. It has evidently just been raised from the seabed. at is also dangerous in a choppy sea, so as soon as the anchor ring breaks the surface of the water it is grabbed with a hook on a block and tackle hanging from the cathead and lifted higher out of the water

The cathead can clearly be seen below the man in the red shirt leaning against the beakhead. If the swell was to smash the anchor, which weighs hundreds of kilograms,

into the side of the ship by the swell it would cause a great deal of damage. at is why a line has been hurriedly attached to the bottom of it to pull it up against the foremost chains, to which a second anchor has already been firmly fastened. A little further aft there is the red anchor buoy, which was always attached to a cast anchor so that it could be recovered quickly if the anchor cable was cut in an emergency. at buoy usually hung in the foremost shrouds, but here it is being hauled inboard through a gun port.

THE OTHER SHIPS

The large ship on the right still has almost all its sails set, but that is changing rapidly, as can be seen from the fore topsail, which is being lowered. Crewmen are scrambling up the shrouds to take it in. Ahead of the bows is another ship with its sails braced back and its head to wind. It appears to be waiting to see what will happen next.

That ship does not have any topgallant masts or sails (the third sails up from the deck), which was unusual for a man-of-war at the time. The ship on the far right is the last one to feel the effects of the change in the weatherheading in from the left, but the unsheeted topgallant on the mainmast shows that it soon will.

The ships of the squadron in the distance also seem to be having problems with the freshening wind, and are all heading into it.

The galliot on the left has turned into the wind and is waiting with flapping sails to see how the situation develops. Two crewmen are securing the jolly boat, which has been brought up alongside, while a third one is steering the vessel. Galliots often sailed with the fleet, transferring people and messages between ships, provisioning them, and maintaining contact with the shore. This one may just have delivered the last members of the large ship’s crew, or perhaps even a commander appointed at the last minute.

FLAGS

Flags are prominent features in depictions of seventeenthcentury ships, and this picture is no exception. A great deal can be deduced from the size, colours and positions of the flags on a warship, but unfortunately their meaning was only fixed from one campaign to the next so as to prevent the enemy from guessing a commander’s intentions. And that means that we, too, are very much in the dark. One general rule, though, was that flag officers could fly a pennant, a tapering, swallow-tailed flag, its position defining the officer’s function within the fleet. The admiral flew his pennant from the mainmast, the vice-admiral from the foremast and the rear admiral from the mizzen.

There is clearly a senior officer on board this ship, and another pennant is visible on one of the ships in the distance.

Van de Velde’s painting evidently shows two parts of a larger fleet coming together. Once the entire fleet had assembled the flags and pennants were modified by agreement between the senior officers.

IDENTIFICATION

The large ship in the foreground is not easy to name, because its transom with the identifying marks on the stern is turned away from the viewer. However, the number of its guns enables several candidates to be selected from the fleet lists, and by a process of elimination after comparing various details of the woodwork it is possible to say with a probability bordering on certainty that this is the Liefde man-of-war. It was built by the Amsterdam Admiralty around 1660 and could mount a maximum of 70 cannon. It had a crew of 270, and served as Michiel de Ruyter’s flagship in 1663. In 1665 it flew the flag of Cornelis Tromp, and was lost on 11 June 1666 under the command of Captain Pieter Salomonszoon.

The other large ship in the painting is showing its stern, and the escutcheon on the taffrail is clearly recognisable as two lions with their backs to each other. ey identify the vessel as the Gouden Leeuwen of 50 guns, which was built in the yard of the Dutch East India Company in 1665.

DATING

On the one hand, then, we have a ship that was wrecked on 11 June 1666 and another that joined the fleet in 1666. The combination of the two pins down the moment depicted in this painting. There can hardly be any other conclusion than that the event is the moment when part of the assembled Dutch fleet was sailing out to meet the enemy in a battle that would go down in history as a glorious victory for the Dutch Republic: the Four Days’ Battle of 11-14 June 1666.

Both ships did indeed take part in the battle. For one it was the first, for the other the last.

Things did not go well for the Liefde. On the very first day of the battle it collided with Tromp’s Hollandia, and then fell victim to a fireship dispatched by the English vice-admiral, Sir William Berkeley, who perished in the action. Most of the crew were picked up in time by the Gouda, including Captain Pieter Salomonszoon, but he died shortly afterwards.

CONCLUSION

Knowing how disastrously the battle ended for the Liefde enables us to view the mood of Van de Velde’s painting with fresh eyes. It is tempting to interpret the dark clouds gathering over the ship as an almost symbolic reference to impending doom.

On top of that, Van de Velde succeeded brilliantly in giving the fairly uninteresting subject of a squadron of ships sailing out on the eve of a major battle such an emotive charge that the viewer senses in advance that something dramatic is about to happen. The vivid scene, the ships pitching and rolling with their massed crews on deck, the whipped-up waves and the rapid turn in the weather are rendered in such a virtuoso way as to make the picture far more than a scene of a departing fleet.

It captures the tension and dynamic movement that is associated with a dramatic act of war. In this case with a battle that is undoubtedly one of the crowning feats of arms in Dutch naval history.

With thanks to Frank Fox, Jim Bender and HerbertTomesen.

Sources

– John Harland, Seamanship in the age of sail, Naval Institute Press 1984.

– Vreugdenhill, List of the fleet of the United Netherlands, Publications of the Navy Records Society, Vol. 85.

– Michael S. Robinson, The paintings of the Willem van de Veldes, Greenwich 1990.

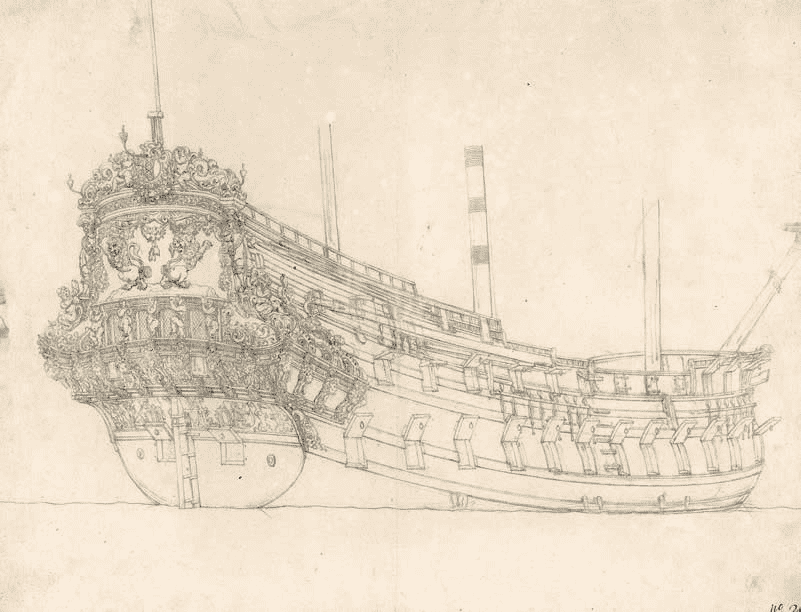

Ships (fig. 15) that were expressly built for warfare were a relatively new phenomenon in the fleets of the Amsterdam admiralties, which up until the end of the First AngloDutch War consisted largely of merchantmen leased for each individual campaign, in addition to the few dozen admiralty ships (fig. 15).

In those days warship design barely differed from that of a merchantman. Maerten Harpertszoon Tromp (1598-1653) wrote a report to the States-General shortly after the Treaty of Münster in 1648 in which he made it absolutely clear that the Republic desperately needed more and larger warships if it was to defend the country and its trading interests effectively, and he added detailed specifications of what was needed. His proposal foundered on the rocks of administrative penny-pinching and lethargy.

The States-General felt that they could always call on the large armed merchant fleet in emergencies, and that they could muster a force of 150 vessels in a short space of time. They deliberately closed their eyes to the fact that the English had been building capital warships known as firstrates since 1636, among them the Sovereign of the Sea with no fewer than 100 guns, as well as the 88-gun Prince Royal, and the Victory, St Andrew, Triumph, Vanguard, Rainbow and St George, all with 60 guns.

As a result, when the First Anglo-Dutch War broke out the English had no fewer than 18 men-of-war that were far more heavily armed than the Republic’s largest ship,the Brederode, Tromp’s flagship, which mounted a mere 52 cannon. The States-General’s 150 ships also turned out to be an illusion. That number remained a dream, and the ships that were offered sometimes proved to be flutes with no more than 6 guns firing stone cannonballs. Going out to face the enemy with that kind of fleet was tantamount

Fig. 15

Reinier Nooms, alias Zeeman

Two large men-of-war

Etching 20.5 x 30.0

H.117 I

Rob Kattenburg Collection

to suicide. So why was the government so unconcerned? It was because of the technique of warfare. A naval battle was not all that different from one on land before the middle of the seventeenth century. After some opening salvos each ship chose an opponent of its own size and then did battle with muskets and pistols, swords, pikes and poleaxes. It did not really matter how many guns you had. Skilled seamanship that enabled you to manoeuvre the opponent into a less favourable position was far more valuable.

The Dutch captains, unlike the English ones, were not chosen for their aristocratic titles. They had been tried and tested at sea since they were young boys, and easily got to windward of their less experienced adversaries. Until, that is, the English admiral Sir Robert Blake (1598-1657) suddenly realised during the Battle of Portland in February 1653 that although he had better ships and outgunned the Dutch he was still losing too often to an enemy that was not nearly as well-equipped for war, on paper at least. It became clear to him that he had to find a way of making more effective use of his strongest point: his firepower. His guns had a longer range than the Dutch ones, and there were many more of them. His solution was the line of battle, with the ships forming up one behind the other and sailing past the enemy, pouring an unremitting stream of fire into them as they went. The Dutch were aghast. That’s not the way to fight a sea battle. But then reality dawned.

You could no longer win a battle by making clever use of wind and currents. There had to be guns. There had to be larger ships. There had to be money. The age of fighting with anything other than tailor-made men-of-war was over. That realisation led to several major fleet building programmes with which the Dutch rapidly made up for lost ground after the debacle of the First Anglo-Dutch War. And for the first time they sailed out to meet their powerful enemies with ships that had been built to wage war, with ratios between length and width that made itpossible to keep the lower gunports open even in poor weather, with efficiently designed quarters for large crews and with the greatest possible number of heavy cannon. It was to turn the tide in the Second Anglo-Dutch War.

The Liefde was one of the last ships to come off the stocks as part of the second shipbuilding programme launched by the Dutch Republic after the debacle of the First AngloDutch War (1652-1654). e specifications were laid down during the war by Maerten Harpertszoon Tromp (1598-1653). The Liefde played an important part in many naval battles, including the action off Lowestoft in 1665, where it was the flagship of Cornelis Tromp (1629- 1691) and was badly damaged. Major repairs had to be carried out, which may explain why the balustrade of the quarterdeck in the painting differs from the one in earlier portraits of the ship, which has been replaced by one that followed an outmoded design. The Van de Veldes were professionals who took the trouble to incorporate such modifications in depictions of their subjects.

There is something odd about the appearance of the Gouden Leeuwen on the right. It is unlike the average manof-war of the period. The difference lies in the placement of the top row of gunports. As was customary in the seventeenth century, the position of the decks was indicated on the outside of the ship by a double row of planks that were thicker than the rest.

They were called wales, and not only strengthened the hull but also gave the ship its beautiful, curved foreand-aft line. at can best be seen at the level of the Gouden Leeuwen’s lowest deck. The closed gunports are clearly indicated above the two bottom wales. But things go a little strange after that. One would expect to find the gunports of the upper deck above the next pair of wales, but they are actually above a third wale, so they are too high up. In other words, the ship’s interior does not match its exterior.

Did Van de Velde make a mistake? that is highly unlikely. The detail in his paintings is so reliable that his works are used as the basis for a great deal of shipbuilding research, and never once has he been caught making a mistake. So what is the explanation for this apparent anomaly?

The Gouden Leeuwen was one of the vessels of the large third shipbuilding programme initiated in the run-up to and during the Second Anglo-Dutch War by Grand Pensionary Johan de Witt (1625-1672) and his brother Cornelis (1623-1672) in collaboration with the Amsterdam merchant and financier David de Wildt (1611-1671) and his son Job (1637-1704).

Since all the work was done in great haste because of the growing political tensions on the international stage, the admiralties also commissioned ships from private yards, simply because their own just did not have the capacity to deliver all those ships in such a short space of time. The Gouden Leeuwen was built at the large yard of the Amsterdam chamber of the Dutch East India Company, and it looks very much as if a couple of building traditions got in the way of each other. Because the gun decks were workspace in a warship, the height between decks was greater than in the average merchantman. It seems that at the last minute the upper deck was built higher up than the shipwright originally intended. And that, in turn, led to another odd feature of the Gouden Leeuwen: it did not have a raised deck over the forecastle, where cannon also usually stood. ere would not have been room for one because of the raised upper deck, so it was simply omitted.

Those modifications, which were made out of sheer necessity, did not prevent the Gouden Leeuwen from having a magnificent career as a participant in almost every naval battle in the years following the moment depicted by Van de Velde. His painting marks the beginning of that chain of events.

Ab Hoving

The Liefde was built around 1660 by the Amsterdam Admiralty. It was some 160 feet long and carried roughly 70 guns. It saw the following service.

– It was De Ruyter’s flagship on his Mediterranean expedition (17 May 1661 to 19 April 1663, when it mounted 60 guns and had a crew of 270.

– At the Battle of Lowestoft (13 June 1665) the Liefde was Vice-Admiral Cornelis Tromp’s flagship as commander of the fifth squadron. The fleet was commanded by Jacob van Wassenaer van Obdam, who was killed in the action.

– On 17 August 1665 Johan de Witt, ‘aboard the ship Liefde’, wrote a letter to the acting pensionary Nicolaas Vevien. e fleet was penned up in the roads of Texel by an English blockade of the Marsdiep. De Witt then personally carried out soundings in the Spanjaardsgat that showed that the channel was deep enough to take large ships. Tje fleet sailed out a few days later and joined up with the fleet off Vlissingen.

– The Four Days’ Battle (11-14 June 1666). e Liefde under Captain Pieter Salomonszoon was part of the rear squadron commanded by Lieutenant-Admiral CornelisTromp on Hollandia. e Liefde had 68 guns. It was destroyed by a fireship on the first day of the battle.

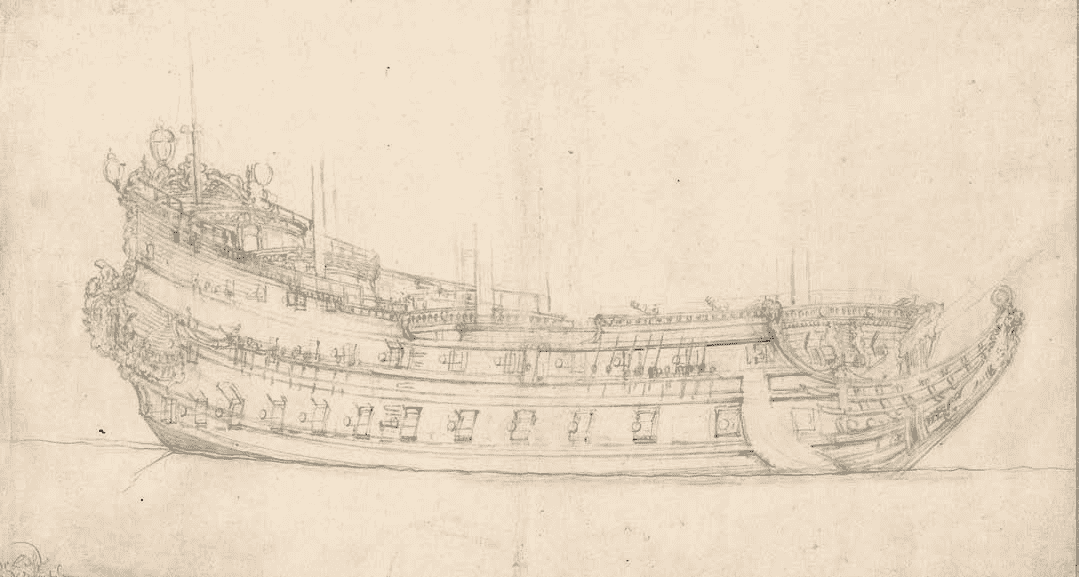

Fig. 16

Left: detail of the Liefde (fig. 5)

Fig. 17

Willem van de Velde the Elder

‘De Liefde’, Amsterdam, first mentioned 1661, 60-70 guns, destroyed in action 1666

Offset, rubbed on the back, with a few pencil additions, 277 x 512 mm

Watermark: fleur-de-lis on a crowned shield

Viewed from before the starboard beam, probably in reverse

Inscribed: ‘de Liefde/ vande Ruijter’; and on the back ‘Schepen van voren & op de zije’.

Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, inv. no. MB 1866/T

252 (PK)

Fig. 18

Ferdinand Bol (Dordrecht 1606-Amsterdam 1680)

Portrait of Michiel Adriaenszoon de Ruyter (1607-1676),

Lieutenant-Admiral

Oil on canvas, 157 x 138 cm

Signed and dated on the right of the balustrade: ‘FBol. fecit. 1667’

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. SK-A-44

Michiel de Ruyter’s career began in the 1620s as a master in the mercantile fleet working for the Lampsins firm of merchants in Vlissingen. He first saw naval service when he was appointed captain of a director’s ship owned by the Lampsins brothers and representing the town of Vlissingen. Ships of this kind fell under the admiralty’ authority but were private warships that were leased and used to convoy merchant shipping. In 1641 De Ruyter sailed as rear admiral on the armed merchantman Haze to

take part in the Battle of Cape St Vincent in support of the Portuguese struggle for independence from Spain. He then returned to his work in the merchant fleet and bought a ship of his own, with which he traded on his own account in the Mediterranean and Caribbean. On the outbreak of the First Anglo-Dutch War in July 1652 the Zeeland Admiralty asked him to rejoin the fleet, and from then on he remained in naval service. His first major action was on 26 August 1652 when, in the absence of Vice-Admiral Witte de With, he was appointed vice-commander (the Zeeland equivalent of rear admiral) and escorted a merchant convoy to Spain. He repulsed an attack by a powerful English fleet of some 40 ships so successfully that it was forced to break off the engagement. He returned home to discover that the action had made his name as a naval hero. From 1652 to 1654 he served under Maerten Harpertsz Tromp and saw action in the First Anglo-Dutch War battles of the Kentish Knock, Dungeness, Portland, the Gabbard and Scheveningen.

After the war, on 2 March 1654, Johan de Witt appointed him Vice-Admiral of the Amsterdam Admiralty. In the years that followed he was sent on various expeditions to the Mediterranean, Danzig and the Sound under the command of Jacob van Wassenaer van Obdam. In 1661 he was ordered to the Mediterranean on the Liefde with a squadron of his own in order to conclude treaties with the cities of Tunis, Tripoli and Algiers that would put an end to the constant threat of Barbary pirates, who were harrying Dutch merchantmen and holding their crews to ransom (fig. 21-22). The expedition lasted until 1653, but within a year of De Ruyter’s return he was sent back again because the treaties were not being honoured. Immediately on arriving in the Mediterranean, though, he was order to sail to the west coast of Africa to retake Dutch forts that had been captured by the English. The final act of this punitive expedition was a crossing to the Caribbean to raid the English possessions there and capture English merchantmen wherever possible. De Ruyter returned home in August 1665 after a two-year voyage. Jacob van Wassenaer van Obdam had been killed at the Battle of Lowestoft, and De Ruyter was now appointed to

succeed him as commander-in-chief of the Dutch fleet, a position that he occupied until his death.

De Ruyter chalked up several victories in the Second Anglo-Dutch War, among them the Four Days’ Battle and St James’s Day Fight in 1666 and the Raid on the Medway in 1667.

Another appeal for his services was made to De Ruyter on the outbreak of the Third-Anglo-Dutch War (1672-1674). The Dutch Republic was now at war with an Anglo-French alliance, mainly with the French on land and the English at sea. On four occasions, at the Battle of Solebay in 1672, the two battles of Schooneveld in 1673 and the Battle of Kijkduin (the Texel) that same year he prevented the English from making a landing from which they could blockade the Dutch coast.

Peace was signed with the English in March 1674, but the Franco-Dutch War went on until 1679. Despite the fact that the Dutch had repulsed his attack, Louis XIV had still not given up his claim to the Spanish Netherlands, and that brought him face to face with a coalition Dutch-Spanish army. As a diversionary tactic he supported a popular uprising against Spain in Messina on Sicily, and De Ruyter was sent to the Mediterranean once more to sort everything out and join the Spanish in confronting the French fleet. The King of Spain had more or less demanded that De Ruyter be the commander-in-chief of the coalition fleet. Before setting sail he had let it be known that he had too few heavy ships with which to keep the French at bay and that he had little faith in the strength of the ships that Spain would be supplying.

In January 1676 the combined Dutch and Spanish fleet met the French at Stromboli, north of Sicily, and they clashed again in April at the Battle of Etna, west of Augusta near Syracuse (Sicily), during which De Ruyter was mortally wounded, dying a week later. He was proved right in his presentiment that his force was too light to overcome the French. Before his departure he had uttered the immortal words: ‘If I am ordered to go with a single ship, and to carry the flag, I should not refuse. Wherever the State wishes to risk its banner, I am ready to risk my life’.

De Ruyter was buried in the Nieuwe Kerk (New Church) in Amsterdam in a monumental tomb on which his effigy lies in front of a sculpted copy of a painting of the Four Days’ Battle by Willem van de Velde the Younger.

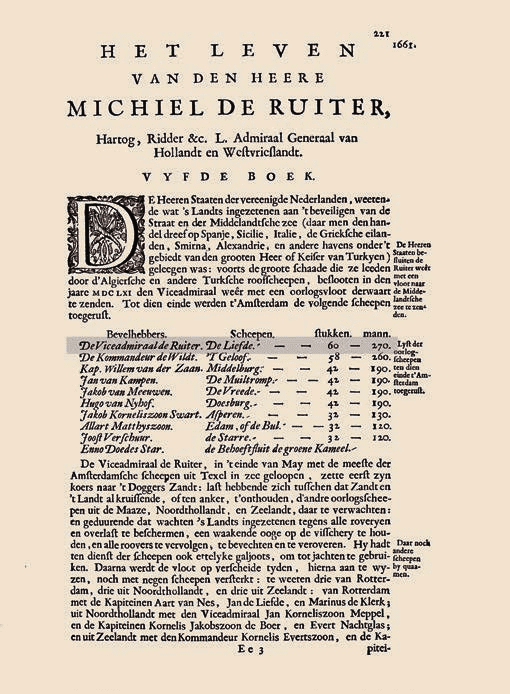

Fig. 19

List of the ships and their commanders at the start of De Ruyter’s

Mediterranean expedition in 1661

From Gerard Brandt, Het leven en bedryf van den heere Michiel de Ruiter,

Amsterdam 1687, p. 221

Fig. 20

Reinier Nooms

View of Algiers with De Ruyter’s ship ‘De Liefde’, 1662

Oil on canvas, 63 x 110 cm

Signed on the flag: ‘R. Zeeman’

1662-1668

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. SK-A-1396

Fig. 21

Bastiaen S. Stoopendael

De Ruyter’s fleet off Algiers in November 1662

From Gerard Brandt, Het leven en bedryf van den heere Michiel de Ruiter,

Amsterdam 1687, between pp. 258 and 259.

Rob Kattenburg Collection

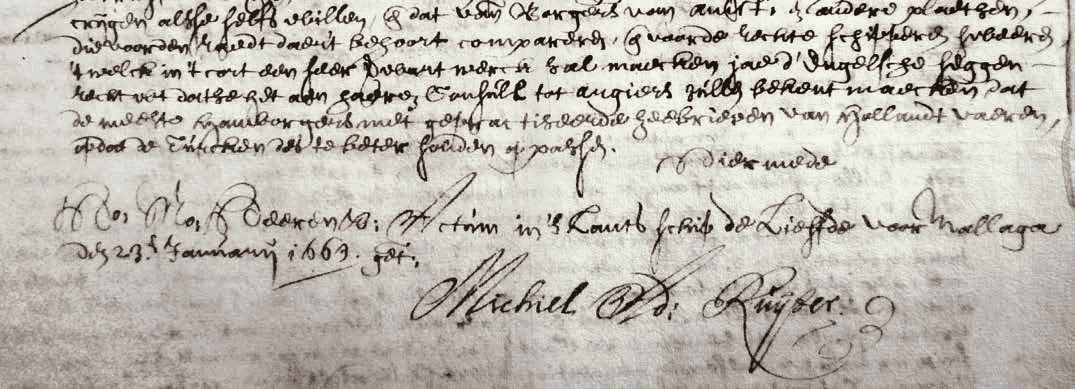

Fig. 22

Copy of a report signed by De Ruyter and written on 23 January 1663

in the port of Malaga, Spain. Hoorn, West Frisian Archives

Fig. 23

Abraham Westerveld (Rotterdam 1620 - 1692)

Cornelis Tromp (1629-1691), Lieutenant-Admiral, in Roman dress

Oil on panel, 40 x 33 cm

Signed at centre left: ‘A.w.’

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. SK-A-1683

Cornelis Tromp was the son of Maaarten Harpertsz Tromp, who was commander-in-chief of the Dutch fleet on several occasions during the First Anglo-Dutch War. He received his training as a naval officer by going to sea with his father from an early age. In 1647 he was a lieutenant and acting captain, and two years later he was made a full captain with a permanent commission. He took part in various battles of the First Anglo-Dutch War and requested to be made his father’s successor after the latter’s death in the Battle of Scheveningen in July 1653. This was not granted, but in November he was appointed rear admiral of the Amsterdam Admiralty, probably in acknowledgement of his father’s service to the nation.

In the 1650s he took part in various actions against the Swedes, and in 1657 escorted a convoy to the Mediterranean. He was suspended from active duty when it was discovered that he had been using warships to trade in luxury goods. He was not recalled until the end of 1662, when he was asked to sail to the Mediterranean again, this time to reinforce De Ruyter’s fleet, which had been sent out earlier to negotiate peace treaties with Tunis, Tripoli and Algiers.

In January 1665, on the eve of the Second AngloDutch War, Tromp was made a vice-admiral of the Amsterdam Admiralty. At the first engagement with the English on 13 June 1665 off Lowestoft he commanded the fifth squadron on board the Liefde (fig. 26). e battle ended in a heavy defeat for the Dutch and the death of the fleet commander, Jacob van Wassenaer van Obdam. Tromp, however, succeeded in bringing the bulk of the fleet safely home, which brought him instant fame. He was made lieutenant-admiral of the Rotterdam Admiralty of the Maze and acting fleet commander. He considered that he had a natural right to be appointed Van Obdam’s successor, but was passed over in favour of De Ruyter, who had returned in August from his highly successful punitive expedition to the west coast of Africa and the Caribbean.The fleet was commanded by De Ruyter during the Second Anglo-Dutch War. After initially refusing to serve under him, Tromp and his flagship Hollandia nevertheless took part in the Four Days’ Battle and the St James’s Day Fight in June and July 1666. However, he was censured again after the latter engagement for pursuing an English squadron, leaving De Ruyter in a highly dangerous and isolated position. He was accused of causing the defeat, and Johan de Witt relieved him of his command, which prevented him from taking part in the Battle of Solebay, the first naval action of the Third Anglo-Dutch War (1672-1674). His fortunes revived after De Witt was lynched by a mob in August 1672, for as a fervent supporter of the princely Orangeist cause he could count on the support of the new stadholder, Willem III (later William III of England). Since Willem had promised Tromp that he would be made commander-in-chief of the fleet after De Ruyter’s death he was prepared to serve again. He fought at the two battles of Schooneveld and at the Battle of Kijkduin (also called the Battle of Texel). However, Tromp was too ambitious and impatient to wait until De Ruyter died, and in 1676 he took service with Danish navy, where he was made fleet commander. On 11 July 1676, in a combined DanishDutch fleet, he defeated the Swedes at the Battle of Öland. It was his only victory as a fleet commander.

After De Ruyter’s death in 1676 and his own dismissal from Danish service Tromp was, as promised, appointed commander-in-chief of the Dutch fleet. He never fought in that capacity, being replaced by Cornelis Evertsz the Youngest in 1684.

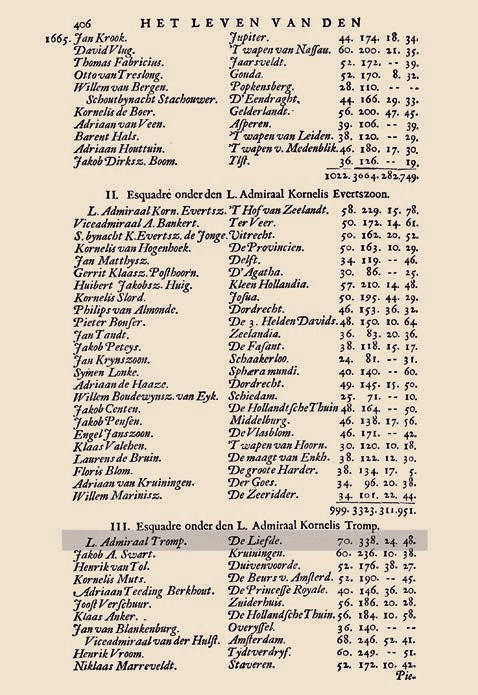

Fig. 24

List of ships and their commanders in Tromp’s squadron in August 1665

From Gerard Brandt, Het leven en bedryf van den heere Michiel de Ruiter,

Amsterdam 1687, p. 406

Fig. 25

Willem van de Velde The Elder, 1665

The council-of-war in the Dutch fleet, 8/18 August 1665

Grey wash, graphite, 201 x 510 mm

Inscribed ‘(dij)nxdach voorde middach de op...’, continuing in a later

hand, incorrectly copying a detached inscription ‘10 junij 1665’,

London, Greenwich, National Maritime Museum, inv. no. PAG6191

Fig. 26

Willem van de Velde the Younger

Calm: Dutch ships coming to anchor

Oil on canvas, 169.93 x 233 cm

Signed ‘W V Velde’ c. 1655

London, Wallace Collection, inv. no. P136

The council-of-war held on board the Liefde soon after De Ruyter’s arrival in the fleet. In the centre, a port quarter view of Cornelis Tromp in the Liefde with flag and pendant at the main (the Liefde Tromp).

The ship in the left foreground flying the flag and pennant of the commander-in-chief of the Dutch fleet has been identified as the Liefde commanded by Cornelis Tromp, who briefly commanded the fleet in 1665. He may have commissioned this painting in or shortly after 1665.

Nothing is known about Pieter Salomonszoon’s early years. He probably worked first as a merchant skipper before being appointed a supernumerary admiralty captain in 1652. At the end of August that year he commanded the Vrede as part of a convoying fleet of 23 ships and 6 fireships under the overall command of Michiel de Ruyter. e admiralty had leased the 40-gun Vrede from the Amsterdam chamber of the Dutch East India Company. De Ruyter’s mission was to shepherd a convoy of 60 merchantmen through the English Channel, but battle was joined when they ran into Admiral Ayscue’s fleet on 26 August. e ensuing Battle of Plymouth was De Ruyter’s first victory as commander of a Dutch fleet.

At the beginning of October 1652 Salomonszoon was still captain of the Vrede when it was part of a fleet of 62 ships under the command of Vice-Admiral Witte de With. During the Battle of the Kentish Knock (also called the Battle of the Zeeland Approaches) on 8 October it soon became clear that the English had the advantage, but De With was able to save the day by seeking refuge among the Flemish shoals.

Salomonszoon is recorded as captain of the 24-gun Hoop from 10 September to early November 1653, which was part of a convoy fleet under De With that was sent to Denmark and Norway to escort 400 merchantmen home.

Salomonszoon was evidently sent out alone on convoy duty in December 1653. e Hollandtsche Mercurius contained a report of some English ships taking an ambassador to Sweden to sign a treaty against the Dutch. When they arrived in Gothenburg one of the English captains discovered that 72 Dutch East Indiamen were waiting below Jutland for a convoy to take them to Amsterdam. They were poorly guarded by a single small vessel with only 20 guns, and before long three of the merchantmen fell into English hands. The remainder cut their anchor cables in order to escape. e report continues: ‘Only the small convoyer captained by Pieter Salomonszoon stood firm’. He began firing on the Goliath, and ‘gave his enemy a broadside’ eight times, damaging it so severely that it had to withdraw. Salomonszoon’s ship was also badly damaged,

but a favourable current carried him to safety, assisted by Danish cavalry on the shore who fired on the English to keep them at bay. The odds were reversed the following day with the appearance of three Dutch warships which recaptured the three merchantmen from the English. And on 31 May 1656, when the Dutch Republic and England were again at peace, the Fazant captained by Salomonszoon was the only convoy ship for ten English merchantmen sailing from the Flemish coast to the north coast of England.

According to Salomonszoon’s own report and that of an English officer, his ship was overmastered in 1 June 1656 by a superior force of Dunkirk and Ostend privateers from which he was unable to defend himself. He himself was wounded and taken to Ostend with his ship and crew.

In June 1658 Salomonszoon is again referred to as captain of the Fazant, which had a complement of 28 guns and 110 crew. It was part of a fleet of 21 ships that was

equipped by the Amsterdam Admiralty and commanded by Michiel de Ruyter.

His orders were to sail to Lisbon and pressure the Portuguese into signing a peace treaty over issues that had arisen in the colonies in the West Indies.

The fleet set sail on 1 June 1658 and reached the Lisbon roads on 4 July. Part of the fleet, including he Fazant, sailed on to Cadiz and then crossed to the Algerian coast in order to root out pirates. The fleet had returned to the Republic by November and December.

In May 1665 Pieter Salomonszoon is recorded in the fleet list as rear admiral on the 54-gun Kampen.

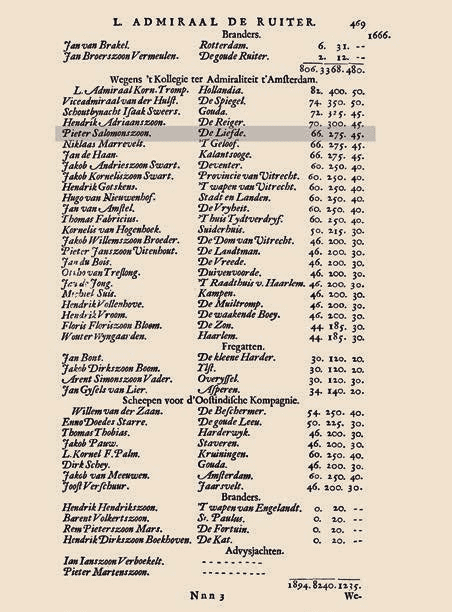

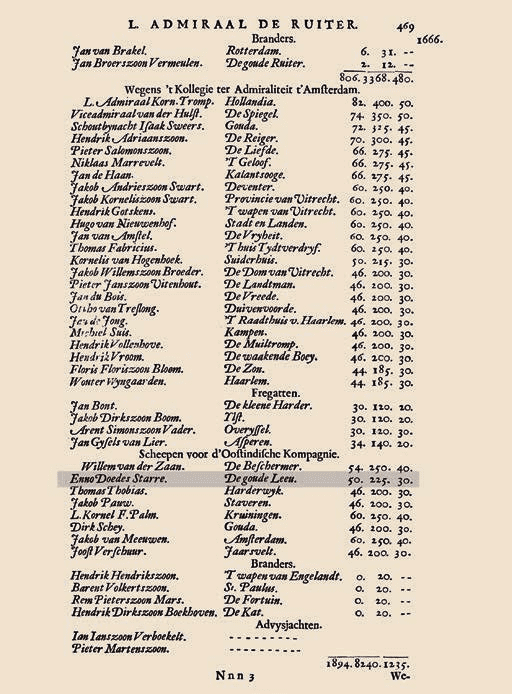

Fig. 27

Fleet list showing Salomonszoon commanding the Liefde in Tromp’s

squadron on 5 June 1666, shortly before his death in the Four Days’ Battle

From Gerard Brandt, Het leven en bedryf van den heere Michiel de Ruiter,

Amsterdam 1687, p. 469

This was shortly before the Battle of Lowestoft of 1 June 1665, the first major sea battle of the Second AngloDutch War (1665-1667). The fleet was commanded by Jacob van Wassenaer van Obdam, and consisted of eight squadrons. Salomonszoon was part of the fifth squadron under Cornelis Tromp, and may have owed his temporary appointment as rear admiral to the fact that he was the squadron’s oldest captain. In 1665 he was again a rear admiral in a fleet of some 65 ships under De Ruyter, to whose squadron he belonged. In mid-August 1665 Salomonszoon commanded the Kampen in a squadron under Cornelis Evertsz.

The fleet was commanded by Tromp in the Liefde, but he had to surrender that position when De Ruyter returned from his expedition to the west coast of Africa and the Caribbean. Salomonszoon and nine other captains had to form a new squadron answering to De Ruyter, who flew his flag from the Delfland. The fleet was

ready to meet the English, but they never showed up. Salomonszoon captained the Liefde from 11 to 14 June 1666 in the squadron commanded by Tromp on board the Hollandia. A massive attack by the English caused chaos in the Dutch fleet, which resulted in Salomonsoon colliding with Tromp. The Liefde was unable to get out of the way of an English fireship and was set alight. Salomonszoon managed to escape to the Gouda, but died of his wounds soon afterwards.

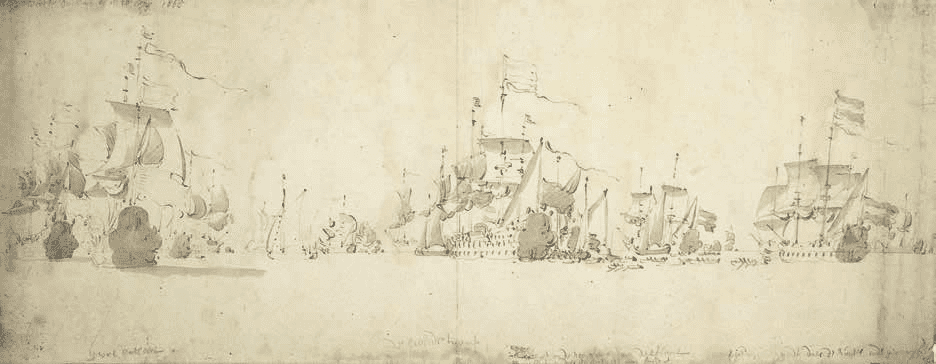

Fig. 28

Willem van de Velde the Elder

Berkeley begins to bear away; the ‘Hollandia’ foul of ‘De Liefde’, Tromp

leaves his flagship, 1/11 June 1666

Pencil and wash, 355 x 680 mm

Watermark: fleur-de-lis on a crowned shield

Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen inv. no. MB 1866/T 86

c (PK)

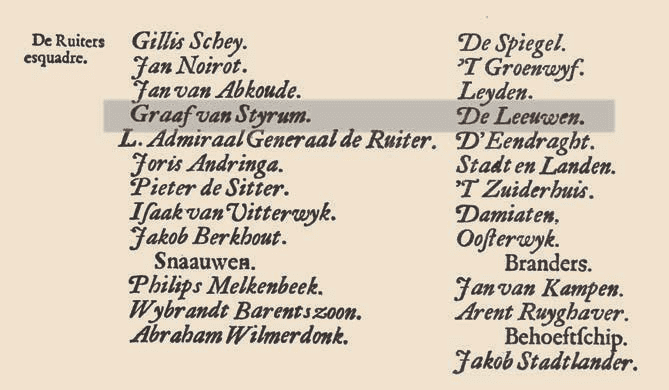

In June 1666 the Gouden Leeuwen was part of a division in the centre squadron of the Dutch fleet under De Ruyter. It mounted 50 guns of various calibres. There were 30 soldiers on the muster roll and 208 sailors and marines, of whom 208 were actually on board. The Liefde is also mentioned in the fleet list for June 1666, with 68 guns and a complement of 45 soldiers and 275 sailors and marines. It was commanded by Pieter Salomonszoon and was part of the Dutch rear under Lieutenant-Admiral Cornelis Tromp on the Hollandia. It was partly due to Tromp’s preparations that the Dutch had perfected the English way of fighting in a line of battle formation, and the fleet of more than 80 ships was divided in the English manner into three squadrons. The centre under De Ruyter consisted of three divisions of around 13 ships each.

His new flagship, the Zeven Provinciën, which had been built in 1665 by the Admiralty of the Maze, was part of the first division, and with its 80 guns and complement of 500 sailors and soldiers was one of the heaviest ships in the fleet. The squadron in the van was commanded by lieutenant-admirals Cornelis Evertsen and Tjerck Hiddes de Vries, and the commanders of the rear squadron were lieutenant-admirals Jan Cornelisz Meppel and Tromp.

On 11 June the Dutch fleet, which was anchored off Dunkirk while waiting to merge with a French relief squadron, was surprised by the English Admiral George Monck, who immediately hoisted his battle ensign and fell on Tromp’s Hollandia. e Danish marine Hans Svendson, who was serving on the Blauwe Reiger in Tromp’s squadron, described in his diary how Monck opened fire first, but missed.