Amsterdam c.1590 – Haarlem 1637 or later

Signed with monogram CVBH on the flag on the mizzen.

Oil on panel, 77 x 121 cm.

PROVENANCE:

The nobleman Philips van Dorp (1587-1652).

Probably collection Cornelis van Teylingen (1590-1658).

The collection of Lars Fredrik Lovén (1844-1939) and Louise Lovén,

née Von Rosen (1853-1937), Linköping. Thence by descent to the

previous owner. Rob Kattenburg collection.

Dendrochronological analysis by Prof. P. Klein shows that the

painting can be dated in or after 1617.

MUSEUMS WITH WORKS BY VERBEECK:

Greenwich, National Maritime Museum; London,

National Gallery of Art; Washington, The National Gallery

of Art; Barnard Castle, County Durham, The Bowes Museum;

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum; Amsterdam, Amsterdam Museum;

Amsterdam, Scheepvaartmuseum; Cheltenham Art Gallery and

Museum.

LITERATURE:

– Ampzing, Samuel. Beschrijvinge ende lof der stad Haerlem in Holland, Haarlem 1628: 372.

– Schrevelius, Theodorus. Harlemias, ofte, De eerst stichtinghe der stad Haarlem, Haarlem 1648 (reprinted 1754): 445.

– Houbraken, Arnold. De Groote Schouburgh der Nederlantsche Konstschilders en Schilderessen, 3 vols. in 1, The Hague 1753: 2:123.

– Willigen, Adriaan van der. Les Artistes de Harlem: Notices historiques avec un précis sur la Gilde de St. Luc. Revised and enlarged ed. Haarlem and The Hague 1870: 20.

– Rooses, Max. “Een veiling van schilderijen in 1616.” Oud Holland 13 (1895): 178.

– Elias, Johan E. De Vlootbouw in Nederland in de eerste helft van de 17de eeuw 1596-1655. Amsterdam 1933: 60-61.

– Bol, Laurens J. Die holländische Marinemalerei des 17. Jahrhunderts. Braunschweig 1973: 45-48.

– Preston, Colonel Rupert. Seventeenth-Century Marine Painters of the Netherlands. Leigh-on-Sea 1974: 15.

– Miedema, Hessel. De Archiefbescheiden van het St. Lukasgilde te Haarlem: 1497-1798. 2 vols. Alphen aan den Rijn 1980: 2:419.

– Doedens, Anne & Liek Mulder, Tromp, Het verhaal van een Zeeheld. Maarten Harpertzoon Tromp 1598-1653. Baarn1989: 15-25, 51.

– Keyes, George S. Mirror of Empire: Dutch Marine Art of the Seventeenth Century. Exh. cat. Minneapolis Institute of Arts; Toledo (Ohio) Museum of Art; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1990-1991. Cambridge, England, 1990: 422.

– Giltaij, Jeroen and Jan Kelch, Praise of Ships and the Sea, Rotterdam 1996: 137-138.

– Vliet, A.P. van, “The influence of Dunkirk privateering on the North Sea (herring) fishery during the years 1580-1650”, in J. Roding and L. Heerma van Voss (eds.), The North Sea and Culture (1550-1800) (Leiden 1996), 150-165, esp. 156.

– Prud’Homme van Reine. Schittering en schandaal. Biografie van Maerten en Cornelis Tromp. Amsterdam & Antwerp, 2001:33-39.

– Paintings in Haarlem 1500-1850. The Collection of the Frans Hals Museum. Exb. cat. Ghent & Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem 2006: 316-318.

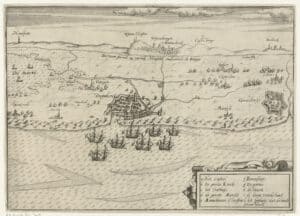

Fig. III

Dutch ships anchored at Dunkirk, c. 1605, anonymous,

1607-1609

Etching, 222 x 310 mm

Rijksmuseum, inv. no RP-P-OB-80.705

Fig. IV

Interior photo of the Lovén home, Linköping, 1897.

The Verbeeck painting can be seen on the right wall.

Fig. V

Profile of Dunkirk 1641

View of the port of Dunkirk

Flandria Illustrata by Antonius Sanderus (1586-1664), 2 vols.,

Amsterdam (Joan and Cornelis Blaeu) 1641

Ghent University Library

As far as is known, this painting of the blockade of Dunkirk, datable around 1630, is the earliest depiction of the subject. Identifying the city in the background is key to understanding the scene. A Dutch squadron of five men-of war in the Dunkirk roads indicates that this is a blockade fleet. Cornelis Isaacsz Verbeeck’s

known oeuvre consists of about 30 small marines on copper or panel, but it has recently been extended with the discovery of this large seascape, which had been in a Swedish private collection for generations.

It is a detailed and colourful panel, and amazingly well preserved. Dendrochronological examination has shown that the panel would have been ready for use from 1617 onwards. The picture is also a rare example of a pupil of Hendrik Vroom equalling his teacher before going his own way in the last years of his life.

This painting depicts the blockade of the Dunkirk privateers’ nest. Four anchored Dutch warships are depicted on the North Sea, with the port of Dunkirk in the background and Fort Mardyck on the right. The fifth warship is depicted in the right foreground with the south wind in its sails. Verbeeck has been particularly

painstaking, and has even taken the wind direction and tide into account. The ship in the left foreground is anchored with its bow to the wind.

The ships all conform to the image we have of vessels that must have sailed between 1620 and 1630: high-sterned with open galleries, wide and round in shape and of an archaic rig, characterised by the many sprouts and crow’s legs of gordings, buoy lines and traps.

This is important for the understanding of the work, because 1621 saw the end of the Twelve Years’ Truce between Spain and the Netherlands, under which the Dutch Republic had been recognised as a sovereign nation since 1609. It is known that many warships were taken out of service after the beginning of the Truce due to

the reduced tension between the two countries. Here we have no fewer than five capital warships, which suggests that the admiralties of the Dutch Republic once again had a large number of ships at their disposal. Indeed, after 1621, a substantial shipbuilding programme got underway to replenish the resulting shortages.

The nobleman Philips van Dorp ordered the panel, with the flagship, the ‘Vlieghende Groene Draeck’, from the Haarlem master, out of pride over the re-established fleet and the successful blockade of the Dunkirk privateers.

Cornelis Isaacsz Verbeeck was born around 1590 in Amsterdam and was registered as a master in the Haarlem Guild of St Luke in 1610. He is known to have been living there in April 1609, when at the age of 18 and residing outside the city walls near the Kruis or St Janspoort he gave a witness statement about a brawl in an inn.

He was nicknamed ‘Smitge’, derived from the old Dutch smijten from his habit of getting into fights. The notorious painter, Rosicrucian and erotomaniac Johannes Torrentius (Verbeek) was his cousin. Cornelis also gained a dubious reputation for his frequent conflicts with the law during his youth. His name frequently appears

in the Haarlem archives, and despite his many run-ins with the authorities he enjoyed success as a painter.

He specialised in small-scale scenes of naval battles, ships floundering off rocky coasts, and beach views, as well as a few largescale paintings of historical events. Verbeeck followed his own nature in having a penchant for depicting ships in a storm. Apart from such fantastic images he painted some topographically accurate views of the kind seen in the present painting.

On 6 December 1609, he married Anna Pieters, also living outside the Kruispoort, in Haarlem. The couple had three daughters and two sons, of whom Isaac would follow in his father’s footsteps.

On stylistic grounds, it is very plausible that the young Verbeeck trained in the workshop of Hendrick Cornelisz Vroom (1566-1640), the founder of Dutch marine painting. The first painter to master Vroom’s style, who probably worked for him for many years, was the Haarlem-born Cornelis Claesz van Wieringen (before 1580-1633).

A handful of marine artists worked in Haarlem, among them Hendrick Cornelisz Vroom, Cornelis Claesz van Wieringen, Hans and Pieter Savery and Cornelis Isaacz Verbeeck,. Together with Abraham de Verwer in Amsterdam and Adam Willaerts in Utrecht, they are among the first generation of painters who made important contributions to the development of marine painting.

Van Wieringen, Vroom and Verbeeck were among the early generation of marine specialists in the northern Netherlands, who specialised in panoramic scenes in which southern Netherlandish idioms were combined with the naturalistic tendencies of the north.

Although the general public has now largely forgotten Verbeeck’s name, his qualities as a marine artist were already being recognised during his lifetime, with his seascapes fetching some of the highest prices in the genre. His marines, furnished with beautifully observed ships, were popular among the citizens of Haarlem, and his name is regularly found in Haarlem painting collections. In 1628, the Haarlem chronicler Samuel Ampzing called Verbeeck ‘heel fraeij en net in schepen-malen’ (‘very fine and exquisite in ship painting’).

Verbeek’s oeuvre, which now consists of about 30 works, shows that he painted mainly on panel and in a small format. He was clearly influenced by Vroom, especially in his treatment of choppy seas with white, hairline spray and deep wave troughs. Verbeeck steered well clear of the monumental sea battles and large harbour views with which his teacher Vroom made a name for himself. By 1630, Vroom was still a popular painter for large sea battles and harbour views, but competition had increased. Besides Van Wieringen, others had also entered the market for naval battles painted in his style. Of these, Abraham de Verwer, who may have

trained in Haarlem, is the most eye-catching. Instead of waiting for commissions he went out and sought work for himself. He successfully offered sea battles that had already been depicted by Vroom and Van Wieringen to city councils, admiralty colleges, trade companies and even an orphanage.

Surrounded by these masters of monumental marine painting, who also painted on a small scale for aficionados and collectors, it would not have been easy for Verbeeck to carve out a place for himself in the market. His last sign of life dates from November 1637, and he is believed to have died shortly afterwards.

It is not known when Verbeeck came to Haarlem. A painter’s apprenticeship usually began at the age of 12 with simple chores in the master’s workshop before progressing to pieces that left the shop under the master’s name. Verbeeck was only able to register as a master in St Luke’s Guild in 1610, the year he turned 21. The mastership opened the way for him to sell his own paintings and to take on pupils, for example, but one gets the impression that Verbeeck was already making good money from painting before then. In April 1609, for example, he was living on his own, and in December that year he was financially able to marry and start a family. Consequently, it cannot be ruled out that Verbeeck did not start out as an apprentice lodging with Vroom but was already an accomplished painter who was attached to the Vroom’s workshop, and perhaps later to Van Wieringen’s after his registration as master. His only dated work, a seascape of 1623 (Cheltenham Art Gallery and Museum), which is mistakenly thought to be of The Departure of the Fleet of Cornelis de Houtman to the East Indies in the Year 1598, proves that he was stylistically still indebted to both masters.

Verbeeck certainly never entered into competition with Vroom and Van Wieringen. He usually painted in what was known as a ‘living room’ size, and mainly served the local market. His earliest known work, ‘a Small Beach with Various Small Ships by Master Cornelis Verbeeck’, is mentioned in a Hague auction catalogue of 1616, but he would have sold most of his work in Haarlem. Some 15 Haarlem probate inventories for the years up to 1675 list no fewer than 23 paintings by Verbeeck, more than half of his presently known oeuvre. In 1622, for example, the yarn merchant Maerten Denijs Verhoeven owned two, possibly three, works by Verbeeck: ‘Een Scheepsschilderij van Cornelis Verbeecq in een swarte lijst, noch een van deselve in een vergulde lijst’, and ‘Noch een scheeps schilderij in een vergulde lijst (‘A ship painting by Cornelis Verbeecq in a black frame, another of the same in a gilt frame’ and ‘Another marine painting in a gilt frame’). In 1636 the child of Jan Pietersz Bossu owned ‘Een groot stuck schilderij gemaeckt bij Mr. Cornelis Verbeeck weesende ’t vuytloop van tessel met een swarte vergulde lijst’ (‘A large painting made by Master Cornelis Verbeeck, being the sea-gate from Texel, in a black gilt frame’). The probate inventory of the Haarlem Nobleman Cornelis van Teylingen of 1658 twice mentions a ‘Principael van Cornelis Verbeeck’ (‘An original work by Cornelis Verbeeck’), which probably means two large pieces of the finest quality. Cornelis van Teylingen (c. 1595-1658) was a true art collector who had a collection of some 60 works by mostly contemporary Haarlem masters, including ‘Een stuckie by Ysack Verbeeck’ (‘A small painting by Isaac Verbeeck [Cornelis’s son]’). Van Teylingen left his collection to his only daughter Maria, who died unmarried in 1664.

Fig. VI

Cornelis Verbeeck (circa 1590-1637)

A Naval Encounter between Dutch and Spanish Warships

Oil on panel, 47.6 x 141.6 cm

Dated between 1618 and 1620

Washington, D.C, National Gallery,

inv. no. 1995.21.1-2

Due to the untimely death of Maria van Teylingen, and the subsequent dispersal of the collection of paintings it is difficult to say which pieces she inherited from her father. Two large and important ones by Verbeeck, a beach scene on panel of 78.5 x 137 cm with two large warships just off the coast, and a naval battle on canvas measuring 92.7 x 137 cm, are now in a private collection in Switzerland and the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich respectively. Both works display flags marked ‘CVBH’, short for ‘Cornelis Verbeeck Harlemensis’.

The National Gallery of Art in Washington has a Naval Encounter Between Dutch and Spanish Warships by Verbeeck on a panel signed ‘Cornelis VB’, but not dated. Despite the fact that it is a battle between several ships, with galleys sinking in the foreground and a Spanish ship suffering the same fate in the far background he chose to depict only one Spanish and one Dutch warship in great detail.

Even the officers, sailors and soldiers on deck are painted almost like individuals with their colourful costumes, their postures and gestures. Since Verbeeck did not date the work and made no effort to define the location of the naval battle or the identity of the warships, which is a common factor in many naval pieces, it is assumed that the battle is a general metaphor for the superiority of the Dutch naval force over the Spanish occupiers. This painting (fig. V) is still in the style of H.C. Vroom. Our painting, showing a Dutch Squadron of five man-o-war at the Dunkirk roads, is probably the first time that Verbeeck was showing that he had distanced himself from the now somewhat old-fashioned style and palette of Vroom and Van Wieringen. It shows a more complex composition and a naturalistic rendering of waves.

The fourth work by Verbeeck, a marine painting on a panel measuring 77 x 121 cm, only recently appeared on the market and has escaped the attention of the art world for more than a century at least. It is extraordinarily well preserved and in almost mint condition. Until recently it was in the collection of the descendants of the Swedish Chief Officer of the Army, Major-General Lars Frederik Lovén (1844-1939), who lived in a country house in Linköping, some 175 kilometres south of Stockholm.

A handwritten label pasted on the back of the panel states, in an old-fashioned hand, that it is a depiction of ‘Goda Hopps Udden’ or Cape of Good Hope, but that identification has been dismissed, for understandable reasons. On one of the flags of the most prominent warship in the foreground is the monogram CVBH. The pennant on the mainmast signifies that the commander of the squadron is aboard. Furthermore the red flag is flying which is the signal to attack.

The sterns of the vessels are not visible to the viewer but the ship left on the foreground can be identified as the ‘Vlieghende Groene Draeck’ under the command of the nobleman Philips van Dorp (1587-1652).

The topography of the landscape on the rediscovered painting was directly reminiscent of the Flemish coast. The identification of the city as the enemy privateers’ nest of Dunkirk, which is supported by various prints with a Dutch blockade fleet in the foreground, is the key to an understanding of the scene.

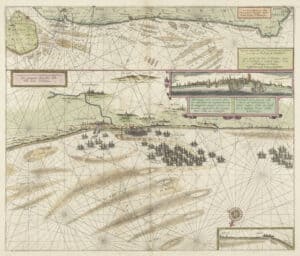

There are many early seventeenth-century prints and maps of the port city of Dunkirk seen from the sea with a Dutch blockade fleet in the foreground. The history of Flemish privateering, especially that centred on the ports of Ostend, Nieuwpoort and Dunkirk, started around 1580. After the outbreak of the Dutch Revolt in 1568, the three Flemish cities sided with Willem the Silent, but in 1580 Nieuwpoort and Dunkirk were first subjugated, and in 1604 Spanish rule was also restored in Ostend. After the surrender of Brussels and Antwerp in 1585, the Spanish also regained control of a large area along the river Scheldt. Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma, came up with a plan to regain the territory for Spain, and he captured the provinces of Holland and Zeeland by making fishing and overseas trade impossible. Due to its strategic location on the English Channel, the fishing town of Dunkirk was transformed in 1582 into a maritime base with its own admiralty subordinate to the headquarters in Brussels.

The Dunkirk Admiralty was mainly responsible for regulating privateering. It included four judges, who assessed whether loot had been lawfully obtained, and numerous officials who on the one hand sold passports or free passes to Dutch and Zeeland fishermen, but on the other hand also distributed loot and held captured crew members to ransom.

Dunkirk fishermen, merchants and shipowners who went on raiding expeditions received so-called letters of marque from the Spanish government that legitimised their actions against the Dutch and Zeeland merchant and fishing fleets. The letter of marque prevented the skipper and his crew from being put to death as pirates if they were captured. No exact figures are known about the strength of the privateer fleet that Dunkirk used as its home port, as many skippers were also freed, but until the beginning of the Twelve Years’ Truce in 1609 the port was the base for some 15 to 20 privateer ships a year. In 1588, for example, 45 ships had been seconded to join the Spanish Armada in its an attack on England, 17 of which had been supplied by private shipping companies.

In order to protect the merchant ships and herring vessels from the raiders, the Dutch admiralties sent convoy ships to guide the fleets through the Channel or escort them to the fishing grounds. At the same time, ‘crusades’ were regularly carried out off the Flemish coast to intercept the raiders at sea. At the time of the Twelve Years’ Truce, privateering had declined sharply because the Spanish had disbanded the Dunkirk Admiralty, but after the resumption of war in 1621 everything returned to normal. In the mid-1620s Dunkirk was re-designated as the first admiralty port and as a new location for the construction of a large shipyard. Just south of the city, construction began on Fort Mardyck to protect the harbour mouth. It was therefore vital that the Dutch not only prevented Dunkirkers from putting to sea on raids but also to make the port inaccessible for the supply of Spanish troops, weapons and supplies. Initially, an attempt was made to destroy the incoming

Spanish ships and escaped raiders by stationing a fleet in the Channel, but its main task was to maintain a complete blockade of all Flemish ports.

Fig VII

Anonimus

Sea chart of the coast of Dunkirk with the fleets guarding the entrance to the port against the departure of the privateers. The Spanish fleet is located in the ‘Scheurtje’. Also a profile of the city, seen from the sea. At the top a smaller map of the Flemish coast from Walcheren to Boulogne, 1631.

Etching 440 x520 mm

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum,

inv. no. RP-P-OB-81.301

Fig. VIII

Portrait of Pieter Pietersz. Heyn (1577-1629)

After Jan Deamen Cool (1589-Rotterdam-1660)

Oil on panel, 68.5 x 51 cm

Dated: 1629 copy of the lost original of 1625

Rotterdam, Museum Rotterdam

Inv. no. 10536-A-B

Fig. IX

Portrait of Luitenant Admiraal Maerten Harpertz Tromp

(1598-1653)

Jan Lievens (1607-1674)

Oil on panel, 115 x 97 cm

c. 1667

Ex-collection Rob Kattenburg

In the 1620s, the States-General sent instructions on several occasions to the five admiralty colleges specifying the number of sailors and soldiers and the type of ships they were supposed to supply to the blockade fleets, but compliance was half-hearted. For example, there was a need for yachts and light frigates that could

lie close to the coast and row, but the admiralty colleges preferred to send their largest ships with a large cargo capacity so as to avoid having to send supply ships all the time. It was also common for smaller ships to leave the fleet to make their way to their home ports. It was only after the appointment of Lieutenant-Admiral

Piet Hein as commander-in-chief of the blockade fleet off the Flemish coast in the summer of 1629 that a certain fleet discipline and uniformity were introduced. The appointment of Piet Hein, who had resigned from the West India Company (WIC) a year before and gained a far-famed reputation as the captor of the Silver Fleet a year earlier, would undoubtedly have played a role in the admiralties’ decision to comply with the new rules.

On 17 June 1629 Piet Hein received the news that 10 privateers had left the port of Ostend and were on their way to harry a Dutch merchant fleet in the English Channel. Hein, who commanded the flagship the Vliegende Groene Draeck, which was built in 1623 and carried 26 cannon and a crew of 125, and with Maerten Harpertsz Tromp as flag captain, set off with seven ships in pursuit. Within half an hour of fighting, three raiders had been captured and the rest had fled. In order not to disturb the other captains, Tromp only announced after the fight that a cannonball had fatally struck Piet Hein. After hanging the imprisoned hijackers against the rules of the law of the sea, he brought Piet Hein’s remains ashore in Rotterdam.

Tromp, who had started his career in merchant shipping, worked in his early years mainly off the Flemish coast. He was appointed lieutenant of the Admiralty of the Maze (Rotterdam) in January 1622 and in January 1624, under Captain Dirck Gerrits Verburgh, he arrived on a ship that was part of the Dunkirk blockade fleet. A year later he was appointed captain himself and was sailing again for Dunkirk in his own ship, the Gelderland. In the following years he was deployed several times in the convoy service, until in 1629 he was asked by Piet Hein to be his flag captain, because of his great skill. According to the chronicler Gerard Brandt, Piet Hein apparently said ‘that he had known many brave captains’ and always found a shortcoming, ‘but never in Tromp, in whom he acknowledged all the virtues that are required

of a sea commander’.

After Piet Hein’s death in 1629, Tromp ran convoy services in the English Channel for many years. In passing, he captured numerous Dunkirk privateers, for which he was rewarded three times with a gold chain of honour. The position of LieutenantAdmiral of the Maze, to which he was not appointed, was his reason to withdraw from naval service for several years. It was only after much insistence that he accepted the position of LieutenantAdmiral of Holland and West Friesland in 1637. The circumstances were not very favourable at the time. There were too few ships available, which made it impossible to convoy the merchant fleet and effectively block the Flemish ports, with the result that on more than one occasion privateers and Spanish transport ships were able to go about their business unnoticed.

It was not until February 1639, when it was announced that 23 Dunkirk privateers intended to break out by force, that Tromp was given the opportunity to prove himself as a naval commander. With only 12 ships he managed to defeat the Dunkirker fleet and captured its flagship. In the same year, Tromp also defeated the Spanish auxiliary fleet or Second Armada, consisting of 67 ships and 24,000 troops, which was on its way to Dunkirk to deliver troops and money. The Dutch fleet lost just one ship, whereas only 18 Spanish ships survived. Dunkirk finally fell in 1646 due to a combined naval attack under Tromp’s command and a French land army. Tromp went on to score many more successes at sea before dying in 1653 in the Battle of Ter Heijde against the English.

Fig. X

Detail of The blockade of the Dunkirk privateers’ nest.

Maerten Harpertszoon Tromp and Philips van Dorp were both incommand of the ‘Vlieghende Groene Draeck’.

Both the Battle of Dunkirk and the Battle of the Downs under Tromp’s command have been depicted many times, and are in some ways the apotheosis of the years of hostilities that had taken place off the Flemish coast since the beginning of the Dutch Revolt.

The nobleman Philips van Dorp was in command of the ‘Vlieghende Groene Draeck’ and in this capacity he ordered the painting. Whether Verbeeck intended The Blockade of the Dunkirk Privateers’ Nest by Dutch warships as a metaphor for this Dutch struggle against Spain, or whether his contemporaries directly associated the great ship off Dunkirk with the flagship, the ‘Vlieghende Groene Draeck ‘of the heroic Piet Hein, Philips van Dorp or the young captain Tromp, is not known.

It is more than 50 years ago that I decided to become an art dealer, and given my fascination since childhood for Dutch maritime history it was almost inevitable that I chose to specialise in seascapes from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries. I didn’t realise at the time that I would be the only dealer in the world to do so. I still am.

A lot has changed in that time. Good paintings have become scarce, and the search for fascinating and historic works costs a great deal of time and effort. But the few times you find a really first-rate work makes it all worthwhile. And that is what has now happened again with a superb work by the talented painter Cornelis Verbeeck of Haarlem.

In my whole career I have never acquired a painting in such a well preserved state. The harmonious composition, refined use of colour and minutely detailed rendering of the ships, rigging and figures make it a feast for the eye.

Fig. XI

Portrait of Admiral Philips van Dorp (1587-1652)

Print by Salomon Savery, after a painting by Rembrandt van Rijn Amsterdam,Rijksmuseum

Inv. no. RP-P-OB-5587

Fig. XII

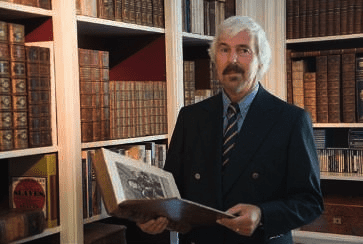

Rob Kattenburg in his library, holding a copy of Geerardt Brandt,

Het leven en bedryf van den heere Michiel de Ruiter, Amsterdam

1687

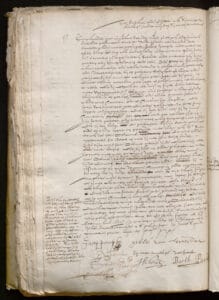

Fig. XIII

1610 Corn: Verbeeck

Noord Hollands Archief 1105 (Craft Guilds at Haarlem), 217

(Names of the members drawn up by L. v. d. Vinne,

16th and 17th centuries, 1677 and undated), letter C.

Fig. XIV

A notarised document signed by Verbeeck. In 1628 he gave a witness statement to the mother of the notorious painter Torrentius, his cousin, who was severely tortured on the orders of the city government.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Production, text and research: Rob Kattenburg

John Brozius

Saskia Kattenburg

Translation Michael Hoyle

DTP Holger Schoorl

Photography Pieter de Vries, Texel

Photo credits

p. 3, 4, 9, 10, 11 and cover: Pieter de Vries, Texel

p. 5, 8, 11: Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

p. 5: Ghent, University Library

p. 7: Washington, D.C. National Gallery

p. 9: Rotterdam, Rotterdam Museum

p. 12, 13: Haarlem, Noord Hollands Archief

This catalogue is published by Rob Kattenburg BV, 2020

The acquisition of the painting was a collaboration between Gallery Rob Kattenburg BV and Kunsthandel P. de Boer BV

Kunsthandel Rob Kattenburg

Eeuwigelaan 6

1861 CM Bergen (NH)

The Netherlands

T. +31 (0) 72 589 50 51

M. + 31 (0) 6 534 05 063

[email protected]

www.robkattenburg.nl

Kunsthandel P. de Boer

Herengracht 512

1017 CC Amsterdam

The Netherlands

T. +31 (0) 20 623 68 49

M. +31 (0) 6 2152 00 44

[email protected]

www.kunsthandelpdeboer.com

© 2022 Rob Kattenburg

Website Mediya.nl