By the mid sixteenth century Habsburg Spain under King Philip II was a dominant political and military power in Europe, with a global empire which became the source of her wealth. It championed the Catholic cause and its global possessions stretched from Europe, the Americas and to the Philippines.

In the 1560s, Philip II of Spain was faced with increasing religious disturbances as Protestantism gained adherents in his domains in the Low Countries. As a defender of the Catholic Church, he sought to suppress the rising Protestant movement in his territories, which eventually exploded into open rebellion in 1566.

The resulting Eighty Years’ War or Dutch Revolt was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish government. The causes of the war included the Reformation, centralization, taxation, and the rights and privileges of the nobility and cities. The Eighty Years’ War, (1568–1648), the war of Netherlands independence from Spain, led to the separation of the northern and southern Netherlands and to the formation of the United Provinces of the Netherlands (the Dutch Republic).

The first phase of the war began with two unsuccessful invasions of the provinces by mercenary armies under Prince William I of Orange (1568 and 1572) and foreign-based raids by the Geuzen, the irregular Dutch land and sea forces. By the end of 1573 the Geuzen had captured, converted to Calvinism, and secured against Spanish attack the provinces of Holland and Zeeland. The other provinces joined in the revolt in 1576, and a general union was formed.

In 1579 the union was fatally weakened by the defection of the Roman Catholic Walloon provinces. By 1588 the Spanish, under Alessandro Farnese (the Duke of Parma), had reconquered the southern Low Countries and stood poised for a death blow against the nascent Dutch Republic in the north. Spain’s concurrent enterprises against England and France at this time, however, allowed the republic to begin a counteroffensive.

By the Twelve Years’ Truce, begun in 1609, the Dutch frontiers were secured.

Fighting resumed in 1621 and formed a part of the general Thirty Years’ War. After 1625 the Dutch, under Prince Frederick Henry of Orange, reversed an early trend of Spanish successes and scored significant victories. The Franco-Dutch alliance of 1635 led to the French conquest of the Walloon provinces and a sustained French drive into Flanders. The republic and Spain, fearful of the growing power of France, concluded a separate peace in 1648 by which Spain finally recognized Dutch independence.

In this Eighty Years’ War or Dutch Revolt there were numerous naval battles fought against the Spanish Empire and some of these memorable events were recorded in maritime paintings, drawings and prints.

THE SPANISH ARMADA

Due to a shared faith in Protestantism, the Dutch and the English would become natural allies. For instance, when the Spanish Armada was dispatched from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by the Duke of Medina Sidonia. He was an aristocrat without previous naval experience appointed by Philip II of Spain. His orders were to sail up the English Channel, link up with the Duke of Parma in Flanders, and escort an invasion force that would land in England and overthrow Elizabeth I. The Duke of Parma was the commander of his land forces in the Spanish Netherlands and the general in charge of the invasion army.

Its purpose was to reinstate Catholicism in England, end support for the Dutch Republic, and prevent attacks by English and Dutch privateers against Spanish interests in the Americas. The result proved to be a naval catastrophe due to a combination of incompetence of the Medina Sidonia, the Spanish Admiral, communication problems with the invasion forces in the Spanish Netherlands, flawed strategy and tactics and appealing weather conditions. The Spanish Armada, in the British channel, also encountered the British Navy, combined to a certain extent, with the forces of the Dutch fleet. In the end, the invincible Armada of 1588 was no more. The defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, is considered one of England’s greatest military achievements and changed the course of European history.

THE ARMADA TAPESTRIES

The Armada Tapestries were a series of ten tapestries that commemorated the defeat of the Spanish Armada. They were commissioned in 1591 by the Lord High Admiral, Howard of Effingham, who had commanded the Royal Navy against the Armada. In 1651 they were hung in the old House of Lords chambers, which at the time was used for the meetings of the committee of Parliament. They remained there until destroyed in the Burning of Parliament of 1834.

The Queen’s Surveyor of Buildings, Robert Adams, had been instructed by Effingham shortly after the battle in 1590 to make maps of the engagements between the English and Spanish navies. The Dutch painter Hendrick Cornelisz. Vroom used these as inspiration for his bird’s eye view designs.

Vroom’s most famous representations of historical naval battles are not paintings but the set of ten tapestries he designed that offered vast bird’s-eye panoramas of the Defeat of the Spanish Armada by the English Fleet. The set was completed in 1595.

The tapestries were woven in the Delft workshops of François Spierincx. Spierincx later supplied three (or five) other tapestries to James VI and I in 1607. The set was later hung in the old House of Commons until 1834 when it was destroyed with the building by fire. The tapestries are known today from a fine set of eighteenth-century engravings by John Pine.

JOHN PINE

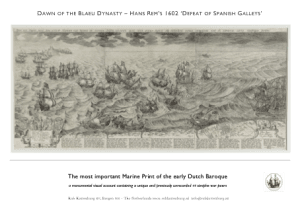

HANS REM

THE DEFEAT OF THE SPANISH GALLEYS 1602

HANS REM, engraver

Antwerpen ca. 1567 – ca. 1620 Amsterdam

WILLEM JANSZ [BLAEU], publisher

Uitgeest or Alkmaar 1571 – 1638 Amsterdam

Defeat of Spanish galleys by and AngloDutch naval force, 3/4 October 1602

In the autumn of 1602 King Philip II of Spain equipped eight large galleys in Seville; these were to set out to the Netherlands under archduke Albert. The main object of sending this fleet was, together with the galleys and warships that were already present, to ‘trouble and constrain the navigation of the coasts of England, Holland and Zeeland, and to close in on Ostend’. Two galleys were lost along the Spanish coast, while the remaining ones were destroyed by a combined Anglo‐Dutch fleet of seven warships in a sea battle on 3 and 4 October 1602. Two galleys were sunk and four were coast ashore on the coasts of Flanders and Zeeland.

As early as 8 November the very same year, the States‐General granted an exclusive five‐year patent to the printmaker and publisher, Hans Rem, allowing him to make, print and sell pictures of ‘the arrival of the enemy’s galleys and how they were rammed and stranded’. Rem dedicated the monumental print to the States‐General and Stadholder prince Maurice. His three sheets depict different stages of the battle, as was customary in broad sheets of this kind.

Although Rem’s legacy is limited – only three prints and a few landscape paintings have been attributed to him – his role in the Amsterdam art scene of the early 1600’s seems to have been crucial. Originating from an Antwerp family of goldsmiths and painters, he’s recorded as Amsterdam poorter in 1594 and was active as a painter, engraver and art dealer.

Willem Blaeu’s first involvement in cartography dates back as far as 1599. F.C. Wieder was keen to remark that ‘there was art and poetry in Bleau’s maps.’ Apart from the scope of cartography Willem Jansz showed a dedication to literature by publishing the work of young poets like P.C. Hooft, Roemer Visscher, Daniel Heinsius, Jacob Cats and Joost van den Vondel. The first years after his installment ‘Op ’t Water’ (Damrak) Bleau had to undergo tough competition from the established mapmakers Cornelis Claesz, Jodocus Hondius and Johannes Jansonius. The latter – Jan Jansz – would eventually become his neighbour. In order to prevent any confusion, Willem Jansz added the name of Blaeu to his patronymic, in honour to his grandfather ‘Blauwe Willem’.

AERT ANTHONISZOON named VAN ANTUM

Frederico Spinola’s failed attempt to break the blockade of Dutch ships at Sluis 26 May 1603

The painting shows, in the middle of the foreground, the Zwarte Galei or ‘Black Galley’ of Dordrecht with the flag of Prince Maurice at the mast and on the stern the flag of Jacob Michielsz. Wip. The galley is attacked by three Spanish galleys, including that of the Vice-Admiral, identified by the Spanish royal coat of arms on the canvas. On the stern of the Dordt galley the red banner is brought down by a Spaniard, while from the crow’s nest of the Dutch galley the Spaniards are violently bombarded.

To the left in the background is the ship of Vice-Admiral Joos de Moor with the Zeeland flag flying. This ship is attacked by two galleys, including that of Frederico Spinola (1571-1603), recognizable by the Spanish royal flag on the mast. Historically this is not quite correct, because according to tradition Spinola flew his flag from the stern, unless this refers to the ship of the Spanish Vice-Admiral, who raised this flag on his mast after Spinola’s death. However, the Spanish Vice-Admiral was not involved in an attack on Joos de Moor’s ship, but was involved in the attempts to overpower the ‘Black Galley‘. The commander is depicted commanding from the stern.

On the far right the ‘Seyl-Hondt‘ of captain Logier Pietersz. is depicted, also with the Zeeland flag. The ship is attacked by two Spanish galleys. To the right of it the Zeeland galley ‘De Flesse‘, recognizable by the red flag with the Vlissingen coat of arms, is firing at the Spanish galleys attacking Jacob Michielsz. In the background, Crijn Hendrickz.’s ship, which could not take part in the battle due to a lack of wind. In the background the Zeeland/Flemish coast with the towns of Breskens, Schoondijk, Oostburg, Cadzand, Sluis, Knokke, Heist and Damme. The crescents of galleys off the coast represent the Spanish scribes at the time they divided into two groups of four.

CORNELIS CLAESZ. VAN WIERINGEN

The present work is a modello, or finished oil sketch, for the composition that van Wieringen was commissioned to paint for Prince Maurits of Orange-Nassau, now in the Maritime Museum, Amsterdam. It depicts the celebrated sea-battle that took place in the Bay of Cadiz on the 25th April, 1607 and which became a crucial event in the history of the Netherlands’ fight for independence against the Spanish. During the Eighty-year War, the Dutch fleet, led by Admiral Jacob van Heemskerck, surprised the Spanish fleet that was anchored off the coast of Gibraltar. Within four hours, Don Juan d’Alvares d’Avila’s entire fleet was destroyed. In the present modello the ship on the lefthand side most likely represents Captain Adriaen Roest’s ship; while to the right of this the two Dutch men o’war under the command of Symon and Cornelis Madder can be seen going alongside the Spanish Vice-Admiral’s three-master. Vice-Admiral Laurens Jacobsz. Alteras’s flagship is depicted on the right, before the coast of Cadiz. It is thought that Abraham de Verwer was also asked to paint a modello for the Battle of Gibraltar.

Provenance: Formerly Rob Kattenburg collection Acquired by the Netherlands, Scheepvaartmuseum Amsterdam.

Exhibited: Amsterdam, Maritime Museum, and The Hague, The Mauritshuis, Terugzien in Bewondering, 1982, no. 95; Rotterdam, Museum Boymans van Beuningen and Berlin. Gemäldegalerie im Bodesmuseum, Lof der Zeevaart. De Hollandse zeeschilders van de 17e eeuw, 1996-97, cat. no. 10

The painting depicts the celebrated sea-battle that took place in the Bay of Cadiz on the 25th April, 1607 and which became a crucial event in the history of the Netherlands’ fight for independence against the Spanish. During the Eighty-year War, the Dutch fleet, led by Admiral Jacob van Heemskerck, surprised the Spanish fleet that was anchored off the coast of Gibraltar. Within four hours, Don Juan d’Alvares d’Avila’s entire fleet was destroyed.

A Dutch fleet of 26 warships was led by Jacob van Heemskerk. The Dutch flagship was Æolus. Other Dutch ships were De Tijger, De Zeehond, De Griffioen, De Roode Leeuw, De Gouden Leeuw, De Zwarte Beer, De Witte Beer, and De Ochtendster.

A Spanish fleet of 21 ships, including 10 galleons, was led by Don Juan Álvarez de Avilés. The Spanish flagship San Augustin was commanded by Don Juan’s son. Other ships were Nuestra Señora de la Vega and Madre de Dios. The Spanish fleet was covered by a fortress, although the Dutch fleet was out of range of its guns at all times and they could not intervene in the battle.

Battle.

THE BATTLE

Van Heemskerk left some of his ships at the bay entrance to prevent the escape of any Spanish ships. Twenty from the Dutch fleet were ordered to focus on the Spanish galleons while the rest attacked the smaller vessels.[2] Van Heemskerk was killed during the first approach on the Spanish flagship as a cannonball severed his leg. The Dutch then doubled up on the galleons and a few of the galleons caught fire. One exploded due to a shot that penetrated its powder magazine. The Dutch captured the Spanish flagship but let it go adrift.

Following the destruction of the Spanish ships, the Dutch deployed boats and killed hundreds of swimming Spanish sailors. The Dutch lost 100 men including Admiral Van Heemskerk. Sixty Dutch were wounded. Depending on the sources, most or all of the Spanish ships were lost and between 350 and 4,000 Spaniards were killed or captured. Álvarez de Avilés was amongst the dead.

The battle resulted in a 12-year truce in which the Dutch Republic achieved de facto recognition by the Spanish Crown.

The battle had an important indirect effect on the History of Ireland, specifically the key event known as “Flight of the Earls”. Hugh O’Neill, 2nd Earl of Tyrone, and Rory O’Donnell, 1st Earl of Tyrconnell, left Ulster in Ireland with the intention of getting a Spanish army to invade Ireland on their behalf. The destruction of the Spanish fleet ruled out any such option, and the Earls found themselves in irrevocable exile – with major consequences for the later history or Ireland, and especially of Ulster.

Attributed to Aert Anthonisz. called van Antum

(Antwerp 1580 – 1620 Amsterdam)

Federico Spinola’s failed attempt to break the blockade of Dutch ships at Sluis, May 26, 1603

Oil on canvas, 138.2 x 244.7 cm

Formerly Rob Kattenburg collection Aquired by the Netherlands Maritime Museum, Amsterdam

The painting shows in the middle foreground the ‘Black Galley’ of Dordrecht with the flag of Prince Maurice attached to the mast and on the stern the flag of Jacob Michielsz. Wip. The galley is attacked by three Spanish galleys, including that of the vice-admiral, recognizable by the Spanish royal coat of arms on the tent canvas. At the stern of the Dordt galley, the red banner is brought down by a Spaniard, while from the crow’s nest of the Dutch galley, the Spaniards are fiercely bombarded with bombs. In the background left, the ship of Vice-Admiral Joos de Moor can be seen with the Zeeland flag flying. This ship is being attacked by two galleys, including that of Frederico Spinola, recognizable by the Spanish royal flag at the mast. So historically this is not quite correct, because according to tradition Spinola had his flag flying from the stern, unless the ship of the Spanish vice-admiral is meant here, who hoisted this flag on his mast after Spinola’s death. However, the Spanish vice-admiral was not involved in an attack on Joos de Moor’s ship, but he was involved in trying to overpower the Black Galley. The commander is pictured commanding from the stern. On the far right is the ‘Seyl-Hondt’ of captain Logier Pietersz. depicted, also flying the Zeeland flag. The ship is being attacked by two Spanish galleys. To its right, the Zeeland galley De Flesse, recognizable by its red flag with the coat of arms of Vlissingen, is directing fire at the Spanish galleys attacking Jacob Michielsz. In the far background is Crijn Hendrickz.’s ship, which was unable to take part in the battle due to lulls in the wind. In the background the Zeeland/Flemish coast with the towns of Breskens, Schoondijk, Oostburg, Cadzand, Sluis, Knokke, Heist and Damme. The crescent of galleys off the coast represents, the Spanish ships’ s at the time they divided into two groups of four.

• Sea Battle between Spanish Galleys and Dutch Warships, 3 October 1602

• A Ship’s Battle, probably Battle of Puerto de Cavite, 12 June 1647

Manila Bay, Philippines